6161 Oak Creek, my mother's childhood hometown, was situated inside of what is now Zion National Park, and covered the area from the Park Entrance and on up the canyon, beyond the present site of the Visitor's Center. Grandmother Crawford, and most of my Crawford cousins lived there.

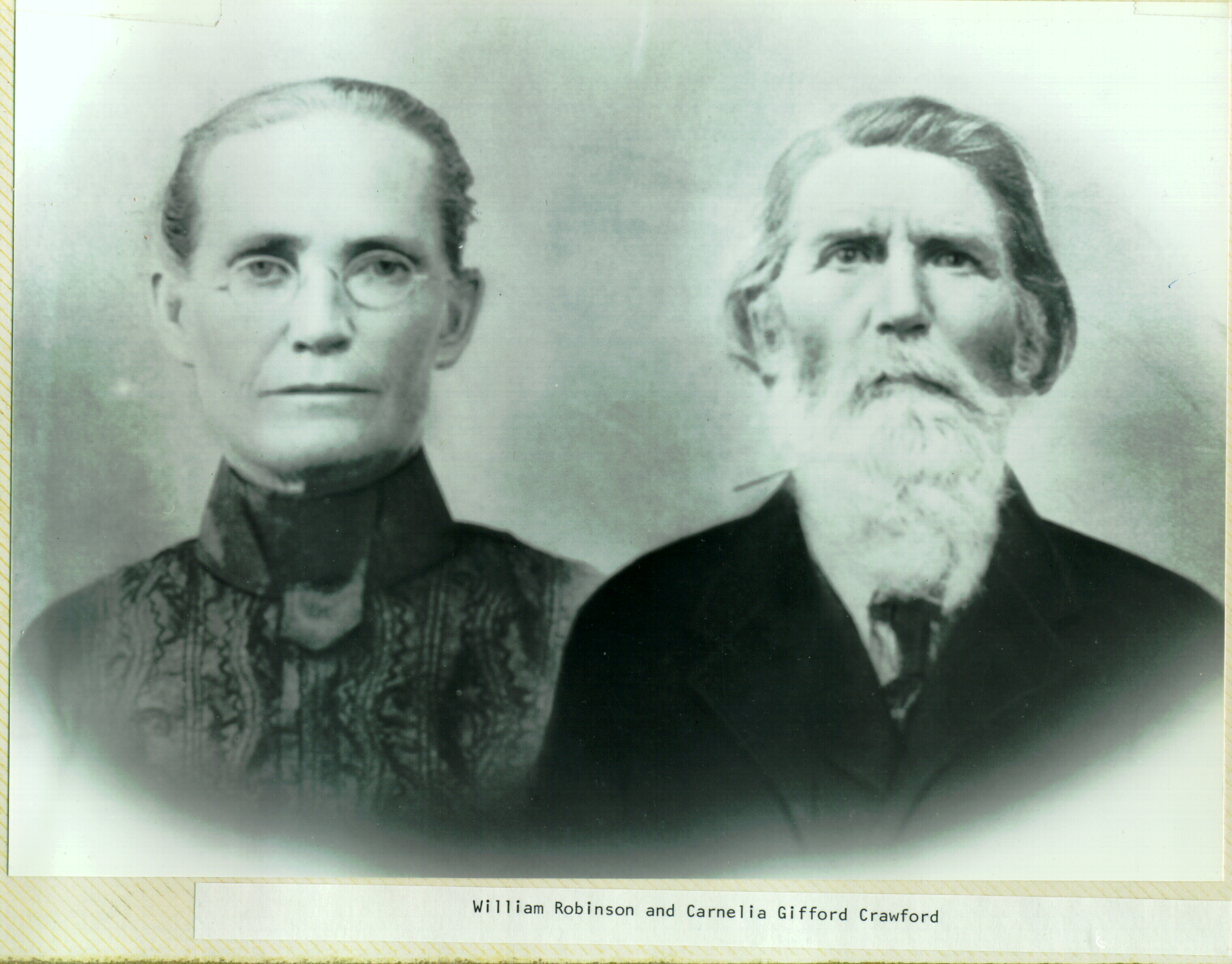

From the J. L. Crawford photo collection in the Special Collections at the Val A. Browning Library, Dixie State College of Utah

Alice's grandfather, William R. Crawford, died in 1913 when Alice was much younger. J. L. Crawford, who collected this and many other historic photographs of Southern Utah and Zion National Park, is one of Alice's cousin, son of Alice's Uncle Lewis—William Lewis Crawford.

"Grandmother" meant Grandmother Crawford, and "Grandma" meant Grandma Isom. That's how we distinguished between the two. Grandmother was as homespun as Abe Lincoln and Grandma was as genteel as George Washington. Grandmother's home was as Early American as Grandma's was Old English.

Thoughts of Grandmother bring memories of her spacious living room built onto the old log cabin. The scrubbed pine board floors were brightened with braided scatter-rugs, and the walls were papered with slick magazine pages, fresh and fascinating, and the windows were hung with calico curtains. A hand-carved mantle shelf topped the fireplace, and on it stood the pendulum clock that had ticked away the years, and standing beside the clock was the kerosene lamp. Currier & Ives pictures hung on the wall, their home-made frames intricate with woodcarvings of oak leaves and acorns. Our Great-Grandfather, Samuel Kendall Gifford, was the craftsman who made the Gifford chairs, and these were the kind used in Grandmother's home. The woven, rawhide bottoms were cushioned with crazy patch, embroidered, velvet pillows.

"Grandmother" is a world of memories to me. It is her calico dress and her checkered, gingham apron with the cross stitch border. It is the blue willowware dishes in her kitchen cupboard. It is Grandfather's two broad-brimmed, felt hats above the kitchen door, giving the impression that Grandfather had just barely hung them on their pegs. It is the spinning wheel upstairs, and the affectionate sound of Aunt Emma's voice as she welcomed us each summer, and the sugar cookies, sprinkled with nutmeg in the blue crock, and cold fried chlcken on a plate. It is picking plump, yellow currants and everbearing strawberries in the garden, and gathering big, brown eggs from the clean nests burrowed into the haystack by the speckled hens. It is the bird-of-paradise blooming by her kitchen door. It is everything that sends my blood racing with the happiness of childhood. "Grandmother" and "Oak Creek" are synonymous to me.

When our uncles from Oak Creek brought their grain to the grist mill, we made our garden hoes smoke, because we could go with them to Grandmother's if we got our weeding done. We rode in the wagon with either Uncle Lewis, Uncle Dan, or Uncle Jim, until Uncle Johnny started driving the mail truck. Then we rode with him.

6262 It was a day's journey by team. The dirt roads were rough and deeply rutted. Dust poufed up from the horses' hooves, and squirted from the ruts as the wagon wheels jogged along, settling thick over us and the sacks of "grist."1 The clopping of the horses and the creaking of the wagon lulled us and we learned to sleep, our heads bouncing against a sack of flour or thumping against the bare boards in the bottom of the wagon. By the time we arrived at Grandmother's house we peered from dust-rimmed eyes, like furry racoons. The water bucket with the gray enamel dipper in it, and the wash basin, soap, and towel were ready for us on a bench by the door. After the first night at Grandmother's, our cousins showed up and it was decided who should have the honor of hosting us for the rest of our precious week.

Our Oak Creek and Springdale cousins were not just ordinary people. They were especially created to live in Paradise. (Oak Creek and Springdale.) Oak Creek and Springdale were only two miles apart and we were related to everyone who lived in both places, except the Langston family. Grandmother had thirteen children, and some of her children had eleven, thirteen, and fifteen children. So we had cousins by the dozens, and every one of them was special in a wonderful way.

Our "up-river" cousins can best be explained by saying they were a part of the canyon, a canyon made deep by towering peaks of brilliant hues. Our cousins were as refreshing as the canyon breeze that came every morning, sweet with the scent of boxelder, and as joyous as the river rippling over rocks. How else can I say how much I loved them? I will introduce those nearest my age.

Elva belonged to Uncle Lewis and Aunt Mary Crawford. She was just my age. Aunt Mary came from the south, bringing with her that southern hospitality. She talked and laughed, and listened to Elva and me as thouch we were grownups. She and Uncle Lewis used to take their hoes and shovels to the field and work together, coming in together at meal time. Each summer, when we were there. Aunt Mary packed the picnic basket while Uncle Lewis hitched up the team, and we would spend one day at Raspberry Bend in Zion. Raspberry Bend is the big bend in the river between Weeping Rock and the parking lot in the Narrows. Grandfather used to have a corn patch there and I am of the impression it was he who originally planted the raspberries. Back to their home in the evening. Uncle Lewis used to sit on the front step and play his harmonica under the stars.

Leata was my age, too, and belonged to Uncle Dan and Aunt Sarah Crawford. Usually, I said "Leata and Elva" in one breath, because these two cousins lived close together and we always played together. Leata was the witty one, reminding me of Edith. Aunt Sarah was fastidious, and Leata could not go to play until the house was shiny slick.

Mary Gifford was a year older than I and belonged to Uncle John and Aunt Fanny Gifford. They lived half-way between Oak Creek and Sprinqdale. I loved to show up at their place just before sundown, because I knew either Aunt Fanny, Ida, Inez or Lella would stir up a batch of corn bread for supper. They knew my insatiable appetite for it, and they always had it when I came. Mary and I used to play on the foothills, down by the river, or through the cane fields together, and Uncle John shared his fresh, roasted peanuts with us. Aunt Fanny became as close to me as though she 6363 were my own age. We never talked much, because she was quiet, but she poured out her inner feelings in letters to me, and always sent cards for no occasion especially, except that it was springtime or harvest time. One card I cherished until the edges became soft and frayed was a picture of a rainbow above an apple orchard in full bloom.

Rupert Ruesch belonged to Uncle Walter and Aunt Marilla Ruesch, who lived in Springdale. He was a year older than I and couldn't really be bothered with girl cousins. But Aunt Marilla's scintillating wit and Uncle Walter's colorful language, made visiting at their house something we wouldn't dream of missing.

Heber belonged to Uncle Sammy and Aunt Emmie Crawford. To get to their place, we went over a swinging bridge across the river. Uncle Sammy was a skilled carpenter, and so was Heber. Heber's miniature barns, corrals,and houses in their back yard were the cleverest I had ever seen, and playing with his spool wagons over the winding roads under the shade trees was cool fun.

Reuben belonged to Uncle Jim and Aunt Ellen Crawford, and he was no more interested in playing with girls than Rupert was. Uncle Jim and Aunt Ellen made up for this default. Uncle Jim used to play his wind-up phonograph for us. The records were cylinder shaped and the sound came out of a big, blue petunia-shaped horn. Aunt Ellen fried up heaps of rabbit meat, golden and crusty. It was good, but I couldn't eat it, because I had spent too much time leaning over the rabbit pen, watching the big-eyed, furry soft babies play.

Norman belonged to Uncle Johnny and Aunt Eliza. He was half-way between Mildred and me, and more interested in her. Aunt Eliza, Susan and Lucy made me feel cuddled and loved. Because they lived next door to Grandmother and Aunt Emma, I felt that their household was one and the same.

Besides the Uncles, Aunts and Cousins, there were Grand-Uncles and Aunts. Especially Uncle Freeborn and Aunt Jane, and Uncle Moses and Aunt Airy Gifford. Uncle Freebom and Aunt Jane ran an ice cream parlor in Springdale. Besides ice cream, they sold chocolates, the old fashioned bon-bon kind that came in wooden buckets. It was wonderful to have a granduncle who had these things, because that made them free to us. I figured anyone who owned a store could have anything they wanted for nothing. Aunt Jane always set us down to a big bowl of home-made ice cream and Uncle Freeborn doled out the chocolates. This was before the days of electricity in Springdale, which made summertime ice cream more exotic.

Uncle Freeborn had an ice pond in Oak Creek Canyon. In the winter he ran a thin layer of water into the pond, letting it freeze. On top of this he ran another layer and so on, until he could saw solid blocks of ice from the pond. He hauled these by team and wagon to his shed in Springdale, and packed them in sawdust. The ice lasted all summer in this insulation.

Sometimes in the summertime, his team would pull into our yard in Hurricane. Packed in his wagon, well-wrapped in ice and quilts, was a five gallon freezer of ice cream to share with ours and Aunt Mary Stout's families.

Uncle Moses bought treats from Springdale, too. Those flour sacks, filled with yellow transparent apples in the spring were mighty welcome. 6464 He used to compose songs and poems to sing and recite at parties. They were humorous and he was a fun granduncle, but sometimes I wished he'd leave Aunt Airy (Aranna) home, for often, when he was at his best, she'd say, "Oh, Moses," in such an unflattering way, and then he'd quit.

I saw little of Mildred during our week together at Oak Creek, for she was off with Merle and Myrtle being a butterfly with the older cousins. She felt beautiful, desirable and free as a butterfly, and that everybody loved her. Consequently, everybody did. All the while, I was having a grubby good time, crawling along on Heber's spool wagon roads, or snagging my dresses on bushes and ledges.

Once Uncle Lewis gave Elva, Leata and me a ripe watermelon. We decided to eat it above the ledges below the Watchman. The melon was heavy, so we changed off often, taking turns carrying it up the steep foothills. The last pitch, lugging the melon past the ledges,was almost too much. Finally, we sat panting precariously above a cliff, clutching our treasure. One of us moved, and the melon rolled out of reach, over the edge of the cliff, and smashed to bits down below.

Swimming in the river in old dresses and bloomers, was a popular sport with the Oak Creek and Springdale cousins. The swimming holes were something more than belly-crawling in the Hurricane Canal. I only had to be pulled out twice to realize that I could swim in knee-deep water only.

Finally came a summer when spool wagons, crawling in the dirt, and puddle wading seemed kid stuff to me. Just before I was fourteen came the glorious, three day, Crawford reunion. I discovered that my uncles and older cousins were amused at my wise cracks, which made my blood race and my head feel keen. I discovered also that boys were fun to flirt with. Even uncles teased in a fun-filled way, especially Uncle Jake Crawford, whom we seldom saw, because he and his family were globe-trotters. His boy Earl was about my age, and very polite. I didn't understand why he always said "Sir," or "Mam," but it had a charm, like reading a book. Aunt Effie's deep blue eyes rimmed with thick, dark lashes, and dark hair was very pretty.

The following was recorded in my diary: "Elva, Venona, Leata, Edith and I hiked up in a canyon east of Uncle Sammy's. We came back with our arms full of beautiful wild flowers and our mouths full of wonderful pine gum.… At meal times there were one-hundred and seven hungry stomachs to fill. It was wash, wash, wash dirty dishes and serve, serve, serve hungry people. Leata, Edith and I gathered peppermint and made some tea. We passed a cup of tea down the table and all of the men smelled it and passed it on until it came to Uncle Jake and he said if we would turn our heads he would drink it. When we looked back, the cup was empty. I told him I didn't believe he drank it, so he put his arms around me and marched me to Mama and said, 'Annie, have you ever caught me in a lie?' Mama said, 'Why no.' 'Well, if you can show me the tea, I'll believe you drank it,' I said and everyone laughed. Uncle Jake took Leata and I with him after he drank our tea, and he was as much fun as a kid."

But this reunion! There were long tables in Uncle Johnny's yard, and someone was always setting it or clearing it. Roving crowds were always eating. I never saw Mama during the whole time, except briefly I learned she never got out of the kitchen, and that she was against three-day reunions.

6565 Carl Crawford had a car—and at last, I was young lady enough to go for a ride with my older cousins. I wore the soft royal-blue satin jumper dress that Grandma Isom had made me. I felt as lovely as a movie star. Carl took us to see the new Rockville Bridge. To give us a thrill, he floor-boarded the gas, and going over the bridge, hit a rut. I was in the bade seat, and was thrown against the car top, skinning my nose against the hardwood bow. My face swelled and went black around my eyes. Worse still, the blue satin dress came apart. It was a tiered skirt, and each tier separated, leaving the cording and satin hanging. Like Cinderella, my finery had turned to rags. There was one saving grace; this was the last afternoon of the reunion.

Footnotes

- Grist was the flour, bran and cereal made from the grain.