(1950)

261261 January 3, 1950. The county assessor, Henry Graff, came by today to express his sympathy for my lone and weary lot. Terry bounced through the room.

"Is that child yours?" he asked.

"Yes," I answered.

"Tsk, tsk, tsk," he clicked, mournfully shaking his head.

Gordon appeared.

"Who's child is this?" he asked.

"Mine," I replied.

"Pitiful. Very pitiful," he sadly said.

When Shirley entered, he asked, "Who does she belong to?"

"To me," I answered.

"What a shame, what a shame," he remarked.

All seven of the children put in appearance, one at a time, and seven times he sadly lamented. I understood his meaning, otherwise I would have burst out laughing. Henry's a kind, good man. What he was trying to impart was, "How pitiful to think their father isn't here to help rear them."

January 7. Terry is going to have his tonsils out. Dr. McIntire asked to check the clotting ability of his blood, so today, Grandpa took us to Hurricane. Gordon and Lolene were with us. Gordon and Terry amused themselves locking and unlocking the back doors of the car.

"Ok, you two, sit down and leave the doors alone," I said.

Gordon obeyed, but Terry kept fiddling with the lock.

"Terry, you're going to get pitched out if you don't sit down," I warned.

Just then the door flew open and Terry was whipped out, his little black coat flapping like wings. Grandpa was going about fifty miles an hour, but it couldn't have been worse if it had been two-hundred. I felt the pain of 262262 the impact as the little fellow hit the hard highway.

"He's gone, he's gone," I cried over and over, frantically watching the distance stretch between us.

It seemed that Grandpa could never stop the car. Far back on the highway, Terry lay in a lifeless little heap. My heart broke, for I was certain that he was dead. Then I saw a truck bearing down on him. Before it reached him, Terry rolled off the highway onto the gravel.

The truck stopped and Cyrus Gifford got out and gathered Terry into his arms. Gordon raced to him as soon as Grandpa's car stopped, and I followed, carrying Lolene who was crying with fright. Terry's coat was splattered with blood from the gash on his scalp. Grandpa looked terribly stricken. Cyrus kept Terry in his arms and rode with us to the doctor's.

In the waiting room I took Terry in my arms. Lolene sat wide eyed on the couch beside me. She pattered close at my heels as I carried her little brother into the operating room. Her head came just under the operating table. She stood silently, close against me all the while I helped the doctor, as he sewed up Terry's scalp. The doctor had more blood sample than he anticipated, and it clotted good.

(In later years, Terry recalls this same incident. He looked down on his lifeless body, laying on the road, in the path of the oncoming truck. His one thought was, "that little kid is going to get run over if something doesn't happen." Then he saw no more. That is when he rolled out of the way. He was conscious when Cyrus picked him up. He recalls feeling sorry that Cy's white shirt was getting bloody.)

January 19. I went to my first town board meeting tonight. Lorin Squire presented us with our certificates of appointment.

January 20. Dr. McIntire took Terry's tonsils out today. He's doing fine.

January 25. Moroni took Rosemary and me for a trip up Toquer canyon to the head of the pipe-line. He explained to us the work that had been done. I begin to feel like a city father.

Our Stake MIA officers had fun at a dancing party at Virgin last night.

February 2. I made Marilyn her first formal—a filmy, pale, yellow one, which she wore to the Gold and Green Ball. I was proud of her, the dress, and of myself, because she looked very pretty. She's been half carrying the torch for Quim ever since their quarrel before Christmas. She was tickled when Neil Hardy asked her to take the dancing course with him from the Church dance director, Mr. Yates. This course has been some of the most wholesome, laughing fun she had for awhile. It's great for her to not be in love, but simply having a good time with the kid that lives down the lane.

Five of my youngsters entered the Quaker's Oats contest, and Gordon, the youngest of the five, was the only prize winner. He received two RCA Victor records, "Lore of the West," by Roy Rogers and Gabby Hays. We've been listening to them morning, noon and night.

February 4.

Grumble, grumble, little lad,

At times you think the whole world's bad.

263263 DeMar's face looked dark as a thunder cloud all during dinner. "I'm not going to dress up for that old school dance," he growled. "I hate dancing. Nobody likes me. All the girls are stuck up. They always say 'no' to me."

"Maybe they wouldn't say no if you combed your hair so it doesn't look like chicken feathers," Shirley said.

"Tell the girls you can't dance any better than a frog, then they'd all want to teach you how," Norman suggested.

"Well, when I do dance, they whirl me around in an old Virginia reel, and I wish I had spikes in my shoes so I could dig into the floor and stand there. I'm going to grow up like Uncle Bill Nielson and never learn to dance."

"Grow up like Daddy. He liked to dance," I said.

Off he marched to school, looking mighty skeptical.

February 15. Ovando said I shouldn't bother farmers about spraying my few fruit trees, or plowing our lot. He says the boys need to learn to work, and they could dig up the garden with a shovel. My, how they would hate the soil if they had to chisel a whole acre of potter's clay that way. We could break our back and blister our hands, and still never dig deep enough to root a squash vine. This lot is total hard pan. I'd give the bottom half to anyone for the next five years, if they'd just tend it.

February 18. Walter Segler came to my rescue. He plowed for us. When I tried to pay him, he just grinned and said there was no charge. I hope this will be recorded in Heaven. I am so appreciative of his help.

February 20. Once, when Winferd was still here, a peddler came to my door. I didn't want his wares, but his wily words interested and flattered me. Before he left, he had talked me out of a loaf of fresh baked bread, a gallon of good Gubler sorghum, and a paper bag of English walnuts in exchange for an unlabeled glass jug of colored water with a little detergent in it. He called it upholstery shampoo. As Winferd came home to dinner, he met the shyster carrying his loot to his car. I told Winferd what had happened, and he laughed at my being taken in by such flattery. Still, he agreed that the flowery words the peddler had spoken about me were true. I was chagrined at my gullibility. I felt like the crowAesop's Fables: The Fox & the Crow that preened on a limb while the fox ran off with the cheese.

Since the incident had amused Winferd so, I thought it might make a good story, so I wrote it up in detail and sent it to the Farm Journal. Today, the manuscript was returned with a rejection slip.

I am the new city clerk. It pays $75 a year, enough to pay my property taxes. I will have to send out about 80 water notices twice a year. Water taxes have raised from $6.00 to $7.00 every six months. Connection fees are $35.00. The town desk is in our living room. Wherever the desk is, that is the city office. We will have town board meeting here once a month, unless the mayor figures we don't need a meeting. I wrote my first big check of $11,361.83 to pay for the new pipe-line the city is installing.

Lolene talks to herself. Sometimes she kisses her hand and says, "Lolene kissed me," or "I kissed Lolene."

264264 Norman, Brent Hardy and Lynn Gubler have been trapping muskrats. One sunk its teeth into Norman's finger. Although it bled good, his hand swelled and made him sick. Dr. McIntire had to clean out the wound. The Canal Company paid each of the boys $4.00 for their muskrat tails. I hope he earns enough to pay his doctor bill.

The cane seed buyer who carried me up the basement steps last spring came today. He was drunk.

When I saw him coming up the steps, I prayed fast, "Help me, please!"

Terry has this terrible talent of giving all who enter here, a pouncing embrace. I've tried to break him of it, but today, this talent was the answer to my prayer. As soon as the man stepped inside, Terry made a dive, wrapping himself around his legs, almost tripping him. This time I didn't call Terry off, but silently applauded him.

The man dug into his pocket and pulled out a dime. "Here, little feller, I'll give you this dime if you'll run outside and play."

Terry took the coin, then backed up and did one of his favorites, a billy goat act, right into the man's padded middle.

Winded, the guy grabbed Terry. "Little boy, I came to see your mother. Why don't you go hoe some weeds?"

Terry backed away momentarily.

"I thought you might be needing a little loving," the man said, coming toward me.

I backed up to a wooden nut bowl on the desk, and closed my hand around the nut picks. I prayed that I wouldn't have to use them, but the grin on the whiskey reddened face closing in on me gave me a firm grasp. The sharp end of the picks were pointed out. As the man reached for me, Terry lunged for his feet, hobbling him. Just then, the school bus stopped. My older children came whooping across the square.

"I've got to be in Cedar within an hour," the man said, then he ambled out the back door.

Heavens and earth! When that man is sober, he is as good as gold!

From the Sunday, 19 March 1950 edition of

Salt Lake Tribune (page 64)

"Fish Story" by Mrs. Alice Gubler, LaVerkin

April 14. Miss Knight brought a flat of stocks for our garden, and Brother and Sister Barber brought flats of pansies, petunias, egg plants and peppers.

Wednesday I got two little checks in the mail. One was from the Deseret News and one from the Tribune for little stories I had submitted for their "It Happened Around Here" columns.

The story for the Tribune is one about George Gibson, Hurricane's barber. It goes like this:

Our barber had a cure for everything, even for the stories of the fish that cot away.

"You used the wrong bait," he'd say. "You can't lose if you use carrots. Get the biggest carrot you can find. Hold it over the side of the boat so the fish can see it. In a few seconds, one will leap. out of the lake to grab it. Quick as a wink, poke the carrot in the hole the 265265 fish jumped through. With the hole plugged up, there's no way for him to get back into the water, so you just pick him up and toss him in the boat."

The story the Deseret News published was an incident that happened to Hilda Hall Bringhurst when she taught school in Springdale, but I didn't know it was her until she called me when the story came out. It goes like this:

From the Sunday, 09 April 1950 edition of

Deseret News (page 95)

"It Happend in the Mountain West" section

"Don't Call Me Names!" by Mrs. Alice Gubler, LaVerkin, Utah

When mother was a child, children sat sedately in their school benches. Teachers were stern and children obeyed. But Springdale's early history boasts of one lad who dared to be different.

It was a frazzled Friday, and the teacher's ire had mounted. In exasperation, she pointed to the lad who had caused so much disturbance. "I warn you not to do that anymore—you—you—you human!"

Bristling, the lad faced the teacher. With quick tears springing to his eyes, he retorted, "I ain't no more human than a pig!"

Yesterday, Emerald Stout came with a message that made my knees wobble. "You're going to be asked to run for the office of county treasurer," he said. "We feel you are the woman for the job, and we can guarantee you all of the votes from the east end of the county. It will pay you $180 a month."

Stunned, I looked at Lolene and Terry standing close beside me. "I can't leave these little ones," I replied, putting my arms around them.

"You've had problems before," Emerald said. "You'll figure this one out."

Left alone to mull this over, I felt awful. Sure, we need the money! But my home, and little ones! I can't leave them.

With little boy enthusiasm, Grandpa Gubler came to confirm the decision of the Republican Central Committee. "I have every reason to believe you can carry the entire county," he said. "You can rent your home and move to St. George."

His exuberance tore me to pieces. After he'd gone, I walked from room to room. Why, this was the only house on earth built to fit us. Winferd had built it! I considered our accumulation, mentally appraising, sorting and discarding. Our furniture is so shabby we'd have to move in the dark.

Then Chauncy Sandberg arrived, the next harbinger of a new beginning. "You'll need to fill out these application papers," he said, "and there will be a filing fee. I had to pay $50.00 to run for State Legislator, but yours won't be so high."

Great. I don't have five cents. The power bill took all I had left.

I'm caught in a whirlwind. Everyone is making my decisions for me. Everyone knows what is best for me, but me! Grandpa came to take me to see the county clerk, Oscar Barrick, before he left for St. George. I shook every piggy bank in the house, and came up with $5.00, which I handed to Oscar.

"The filing fee for county treasurer is $21.50," he said.

I felt like a roof tile had fallen on my head. "Just a minute," I said. My throat tightened. Going to the car, I said, "Grandpa, I don't want to file for office. He wants $21.50. It's like betting on the horse races. If I lose, I don't get my money back. The $5.00 I brought isn't even mine."

266266 "Well—," Grandpa drawled, "I'll pay the fee myself, before I'd let you not file."

Taking his check book from his pocket, he wrote out the needed amount.

"You'll never get that money back in kingdom come," I said.

"I don't care," he grinned. "You'll win."

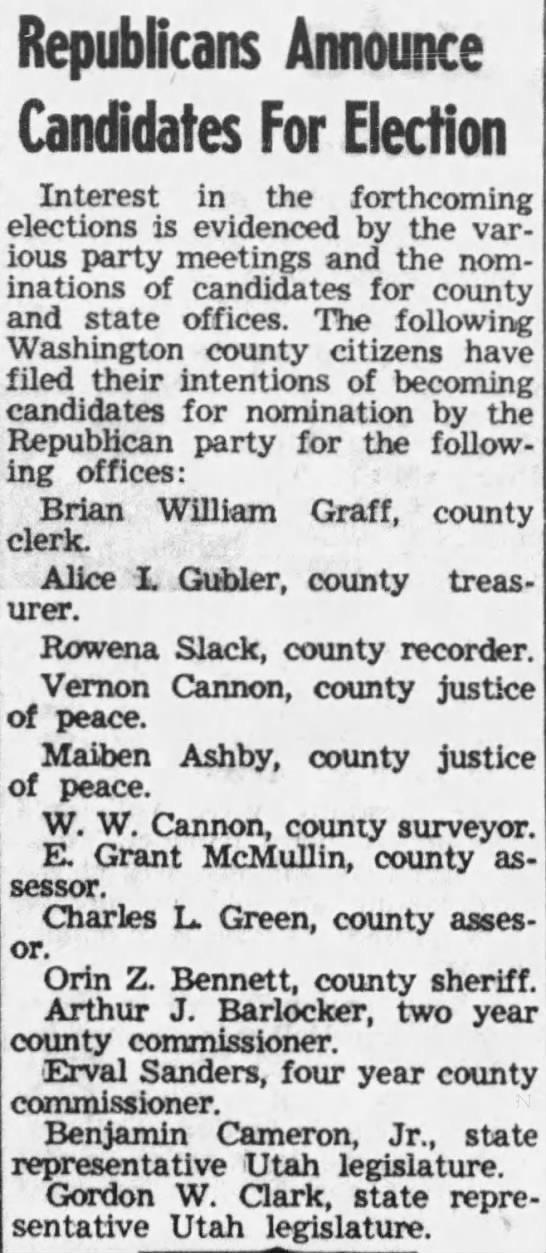

From the Thursday, 20 April 1950 edition of

Washington County News (page 10)

Republicans Announce Candidates For Election

"... Alice I. Gubler, county treasurer."

April 21. My intention to run for County Treasurer has been published in the County News. Free advice and criticism begins to pile deep. Why don't I stop being so stupid, and just stay home and accept county aid. People say I'm an idealist—clinging hopefully to the powers of providence, that I'll come down off my high horse. Well, we aren't starving to death. Sure, the family and neighbors have helped us. I just simply do not want to accept public welfare. So now I'm being harangued, harassed, and harried.

Emil Graff has given Marilyn a job clerking in the store after school each day, and the bishop has given Norman a job watering the shrubs on the church grounds. I'm thankful for that.

I had refused to take students as guests during the school music festival, but I had a change of heart. Yesterday morning I routed the family out at 6:00 a.m.

"I guess we'd better put a couple of girls in your room," I said to Marilyn.

She leaped out of bed. "I'll wash my windows and put up clean curtains." And she did.

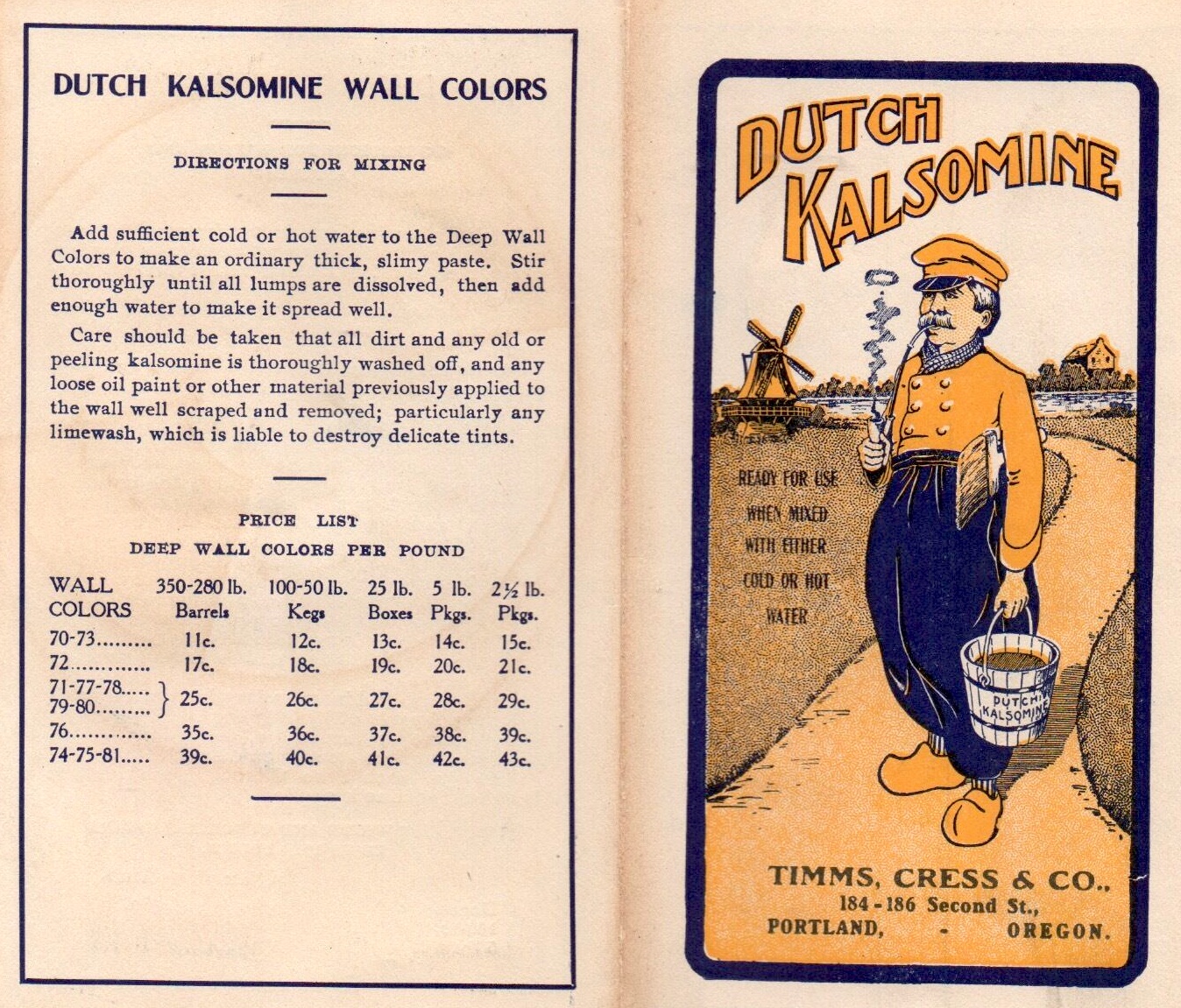

The boys finished planting our little trees, while Shirley and I washed woodwork. This morning, Marilyn and Norman kalsomined the hall before school, and Shirley did the dishes as though she enjoyed it. I did the laundry and called the plumber. Ever since Halloween, we've flushed our toilet with a bucket from the bathtub. Tonight the house shines, supper was a success, and the place rings with the laughter of my children and our guests.

An ad from the 1920s for a kalsomine paint or whitewash

See Wikipedia's article on Whitewash.

If it hadn't been for the music festival, I guess we'd have been flushing our toilet forever with a bucket, and have ignored the finger prints on the hall walls.

May 2. Lucille Gubler needed to go to St. George today, so she took us to the dentist. Dr. Hutchings checked all of the children.

DeMar, Gordon and Terry went to Pickett's with me to get some new mush dishes. We're always out. I had $1.50 to buy them with.

"Let me carry them, Mother," Terry begged.

"No, I want to," Gordon said.

"No. DeMar will. You kids might break them," I said.

So DeMar took the precious package. We walked down the street to meet our car. As we waited in front of Penny's store, DeMar restlessly hitched the package from one hand to the other. The string came loose and the package crashed to the pavement.

"Oh, DeMar," Gordon shouted.

DeMar fell to his knees and pulled back the brown wrapping. The top dish fell apart in his hand. Down through layer after layer the same thing happened. One dish out of the dozen was not broken. It was only chipped. 267267 Big tears welled up in DeMar's eyes.

Lolene kept repeating loudly, "DeMo boke em. DeMo boke em."

"Now we can't have any new dishes," Terry lamented.

I noticed a young man sitting in his car, his three children climbing over him. Mournfully, he surveyed our little group, shaking his head from side to side. We were creating a scene, so I grabbed up the wreckage, and we moved on.

From the Thursday, 11 May 1950 edition of

Washington County News (page 5)

LaVerkin news by Mrs. Pearl Henroid, Reporter

See the last two paragraphs.

May 12. Five days have passed since Doom's Day. At last I'm out of shock enough to make a diary entry.

Vida Duncan took me to Union Meeting at Springdale in her pickup Sunday. I had a notion to take all of my boys, but DeMar and Terry were the only ones on the spot when she honked her horn. Gladly they piled in the back. Well, really, I shouldn't expect the sky to fall in the two hours that I would be gone, and it didn't. But it might as well have.

While DeMar and Terry were having a happy time on the school slides in Springdale, and I sat in church, Norman and his buddies were enlarging their underground house beneath the cherry tree at the bottom of the lot. I've reared a batch of gophers. My youngsters have been grubby with red clay for weeks, as they've burrowed in and out of their diggins. If I had asked them to excavate a basement by hand, they would have rebelled, but the rooms in their underground house were growing to impressive proportions.

Little did I know of the sticks of dynamite that had been concealed in our old house ever since the day the deacons gathered asparagus for the cannery. While scouting the fields, they found some dynamite, so they hid it under the asparagus , then stored it for this momentuous day and hour.

The day was May 7, the hour 4:00 p.m. All of the saints were safely and peacefully home from church, except the extra-milers who were at Union Meeting.

When I got home, the whole town was at our house to greet me. Little kids swarmed like flies, trooping along with me toward the house until I could hardly step.

"Look, look, your house is blowed up," they chorused, pointing to the gaping hole in the ceiling.

Grownups, shaking their heads and clicking their tongues, regarded me with horror and pity. Shirley lay white on the couch. A flying clod had knocked her down. Something terrible had happened. Just what, and how terrible, I did not know, because everyone was talking at once.

I went into shock. I couldn't speak. The day was a hot one, but I was freezing. I shivered and shook, and my chin chattered. Out of the babble, I caught snatches of words, "dynamite," "biggest blast that has ever rocked the town," "scrap iron spewed from the cherry tree," "field showered with flak," "a dozen kids almost mowed down," "Gordon came closest to getting hit with flying iron."

Gordon was standing innocently in front of the little old house, unaware of what the older boys were doing, when a big scrap of iron whizzed by.

268268 Neil Hardy didn't want to be any part of the excavation, so he sat down in our living room with a stack of funny books. When the blast shook the house, he ran to the door. A minute later, a red hot iron, the splintered part of a wagon axel, crashed through the roof, bringing a pile of plaster with it, and landed on the couch in the exact spot where Neil had been.

This episode could have been mass slaughter, but it was not.

"Was anyone hurt?" I finally managed to ask.

"Not that we know of," someone answered. "We haven't seen Norman or Rulon since the blast."

"Oh," I groaned, "they might be dead. We've got to find them."

While the multitude lamented my damaged home, Lyman and Thell Gubler were out on the roundup, accounting for the boys. This is what really mattered. Norman and Rulon had climbed a pear tree in Grandpa's orchard, hiding in fright. Lyman personally let them feel the whack of his shoe.

Now, five days later, Cyrus Gifford and Harris Merrill have mended my roof and plastered the hole in the ceiling. The scar is still there, and the town still feels the tremors of the after-shock. Since our house sits in the center of town, it is quite fitting that we should be the center of attraction. And we are. Crossing our threshold daily are visitors who come to sympathize, lament, complain, condemn, to be horror stricken, to be amused, to laugh and wise crack, and to tell me how to raise kids. I do appreciate Orin Hepworth for taking Norman into his counsel, to explain and to help him understand about explosives. Orin is experienced, and able to give good, honest advice.

The underground house, incidentally, is now a crater.

May 16. This evening we spread our supper on an army blanket out on the lawn. Neil Hardy was having supper with us. After the fried chicken was devoured, Marilyn ran in the house for dessert dishes. We had plum cobbler, baked in a large milk pan. With a whoop, Marilyn burst through the front door, and leaped from the porch to the lawn. One foot landed in the middle of the cobbler. She squealed and hopped out, and everyone groaned.

"Oh well," she giggled, debating whether to wipe her shoe on the grass or whether to lick it, "I've never had all of the cobbler I wanted anyway. I'll eat my track."

With a tablespoon she scooped out her track, heaping it onto her plate. Neil turned sick to his stomach and went home. By the time we divided the untouched narrow rim of cobbler that was left around the pan, the servings were small.

May 23. Early yesterday morning, as Norman hoed alongside me in the garden, he started to complain.

"My neck pops every time I turn my head. It gives me an awful headache."

That was the introduction. With each swing of the hoe it got worse. He stopped and rubbed the cords of his neck often.

"I need to go to the chiropractor. Something is terribly out of place."

"Chiropractors are a lot of nonsense," I said.

269269 "But I can't do a thing this way," he insisted. "Pansy is taking Paul to St. George this morning and she said Neil and I could go too. I told her my neck was out of place."

Dropping my hoe I said, "I'll go see her."

As I got to her gate, the thought struck me. Of course Norman's neck was out of joint. Neil and Paul were going to St. George and he couldn't go with them. They were already gone, anyway, so Norman and I hoed on.

He concentrated so much on his neck that the pain became real, so I borrowed Grandpa's car and took him to the doctor for a physical.

McIntire checked him thoroughly. "You're fit as a fiddle," he said. "Instead of your mother paying this bill, why don't you stay and hoe for me? I'll pay you 50¢ an hour."

So Norman is hoeing for McIntire—six hours of it, to pay for his $3.00 pain in the neck.

June 29. DeMar broke his arm three weeks ago. He was playing with friends upon the hill, when the rock he was on went out from under him, and he fell over a little ledge. Roy Wilson brought him home in his little express wagon. The bone was so badly splintered that Dr. McIntire couldn't set it, so I had to keep the arm in ice packs for a week until the swelling went down. Then we took him to the Iron County Hospital, where Drs. McIntire, Brodbent, Edmunds and Dan Jones worked on it. Sitting in the waiting room seemed an eternity to me. DeMar was mighty sick when he came out of the ether.

July 7. A Whiffle McGoof is an eerie creature that wears a witches cape, and climbs fruit picking ladders up to roof tops when mothers are at Stake meetings. A Whiffle McGoof makes little girls and boys afraid to go to their basement bedrooms, until worn out, they finally fall asleep on the living room couch until Mother comes home. I feel very cross about Whiffle McGoofs, especially the ones named Marilyn, Norman and DeMar. Lolene wraps her little arms about my legs until I can hardly walk, whenever I leave the room, and Terry comes crying back into the kitchen after I've sent him to bed, and I keep finding the basement screens pulled off. There is no excuse for scaring little kids!

The latest Whiffle McGoof episode is the trap door built in the top of the living room closet. This has been accomplished while I was away. With much moaning, a terrifying creature partially descends from on high. Until Val Jennings discovered the true identity of a Whiffle McGoof, this act sent him scurrying across the square toward home. I've had to banish all such creatures. I haven't forgotten the cruel torture of being frightened when I was a child.

July 8. "Owe, owe, owe," Terry howled, running in through the kitchen door.

"Serves him right," DeMar said. "He should know by now not to shut bees in squash flowers."

"I know it," said Gordon, "because he doesn't know how to hold them without making the bees mad."

270270 July 11. Frank Stevens is working for his uncle Elmer Hardy this summer. Whenever his truck, tractor or spray machine comes up our road, it stops, and Frank whistles like a squirrel. My boys stampede to greet him, escorting him to the house like a king with an armed guard. Since there are only seven evenings a week, that's all that he spends in our yard strumming Garn Segler's guitar, which Betty left here three months ago. Both Betty and Marilyn have shared the strumming, singing, the moon and stars, then along comes Frank's dashing uncle Chance Hardy. Chance has been in the navy and seen the world. Chance services Union Pacific Trains, and has money in his pockets. He drives a motorcycle that's as dolled up as Roy Roger's horse. Flashy. Chance is flashy too. He's handsome. He's a lady's man. Frank paced through the house a number of times on the 4th of July, only to learn that Marilyn was off with his uncle. Like a squatter on his homestead, Frank stays.

July 18. Chance still has the upper hand. Frank comes to see Norman now days. I wish Marilyn was 20 and safely married to a good man. I'm too tired to be a mother.

Yesterday was my birthday. Among my gifts was a dead beetle from Terry and a firecracker from Betty, a motorcycle ride from Chance and a ride during a thunderstorm with Wayne, Mama, Papa and my littlest children. We went to see the flood over the Third Falls. After Town Board meeting last night, Wayne and I went to see Bob Hope in "The Great Lover." It was funny.

From the Sunday, 04 June 1950 edition of

Deseret News (page 95)

"It Happend in the Mountain West" section

Too Cold by Mrs. Alice Gubler, LaVerkin, Utah

July 23. The Deseret News sent me a check for two more little stories. One was a summer day incident when I gave my little niece Elda Judd, an ice cube to lick.

When her fingers became aching and red, she said, "Aunt Alice, isn't there some way you can warm this ice a little?"

The other incident was about a little boy who knocked on my brother Bill's door one morning. "I'm not a baby anymore," he said. "I'm a barn."

"A barn?" Bill asked in surprise.

The little boy nodded. "Mama says I'm her first barn, and my baby brother is her second barn."

September 15. The bishop asked our family to clear the tumbleweeds from off the church grounds. Monday we were all busy with our shovels and hoes when Terry struck a yellow jacket's nest. The wasps covered him solid, and he screamed in pain. I grabbed him and ran, swatting off the stinging insects, then they swarmed on me. Swiftly we ran home. I dumped a whole package of soda into the bathtub and plunged Terry into the water. He swelled like a blimp from the top of his head to the bottom of his feet. He had no eyes, no facial features, no neck. He was one solid hunk of swollen misery. He was so filled with toxin that he could hardly breathe or even cry. He would never have lived if the elders hadn't come and administered to him. How grateful I am for the power of the priesthood.

The wasps didn't sting my face or neck—only my arms and legs. This was pure torture. My limbs were swollen shiny tight. We got udicane—prescription strength—from the drugstore. Applied every four hours, this ointment numbed the flesh so we could endure while the healing took place.

From the Sunday, 27 August 1950 edition of

Deseret News (page 91)

"It Happend in the Mountain West" section

New Title by Mrs. Alice Gubler, LaVerkin, Utah

271271 October 14. Tomorrow is the ward fair. We've made cakes , candy, and aprons for the bazaar, and have garden produce ready for the auction. But as usual we're broke.

"Let's stay home tomorrow and can beans," I said to my children, "The booths and side shows are set up to raise money, and we haven't any."

Marilyn and Norman said nothing, but a wail went up from the other kids.

"Please don't go up there and stand around wishing. It's embarrassing if you have nothing to spend."

Shirley ducked into the hall and sobbed, "It wouldn't be like that if Daddy was here."

"But Daddy isn't here. We pay our tithing and do the best we can, and now it's up to the Lord."

Just then Bill Stratton knocked on the kitchen door. "They tell me you have some molasses cans you'd like to get rid of," he said.

"We sure have," I replied, leading him into the old house.

Bill bought $11.00 worth.

Gordon's eyes were big with wonder. "Mother," he exclaimed, "you just said it's up to the Lord and there came that knock at the door."

The children were all smiles. Tomorrow, we will go to the fair.

October 29. The political campaign is on. With the other candidates on the Republican ticket, we've knocked on every door in Enterprise, Veyo, Central, Gunlock, PineValley, Ivins, Santa Clara and Hurricane.

I dreamed, the other night, that I was walking along the highway alone. Crowds passing on foot and in cars, pointed at me and laughed. Looking down, I saw that my underpants had fallen around my ankles. Embarrassed, I recalled the jingle, "Oh, it's hard to grin with ease, with your step-ins slipping to your knees."

The next day—and this is no dream—Gordon Clark and I were political tracting in Santa Clara. He took one side of the highway and I the other. At the end of my street was a service station, and then about a quarter of a mile further on was an isolated dwelling. As I hiked alone, streams of red-capped California deer hunters drove by. And then, like in my dream, I felt like people were laughing at me. With a horrified feeling, I realized something was hobbling me. Looking down, I beheld my pink skirt was unzipped, and about a foot of white satin showed between it and my blouse. My purse and armful of literature occupied both hands. Eeeek! What to do!!! The traffic ceased just long enough for me to lay my stuff down on the road and zip up my skirt. As I picked up my load, cars began streaming by again. What a funny parallel to my dream.

November 4. Marilyn and Norman went with me to a Democrat rally last night. I enjoyed it, until the chairman, Mr. Miles, introduced Nettie Morris, my opponent.

"We're concerned about the office of County Treasurer," he said. "We feel it is too important an office to turn over to a newcomer just because of our sympathy. Mrs. Morris is capable, experienced, etc. etc. etc. Her opponent should be permitted to remain at home to care for her family. 272272 There are welfare organizations set up to take care of such people.…" On and on he went about that pitiful little widow in LaVerkin.

Marilyn leaned over and said, "Mother, them's fightin' words, ain't they?"

"They sho' is," I whispered back.

I didn't like any more of that rally.

From the Thursday, 09 November 1950 edition of

Washington County News (page 1)

Washington County, Utah Election Results, 1950

November 7. Election day. I got a little hostile at one of the judges of election, when I went to vote.

"Just what right do you have running for office with a family the size of yours?" she asked. "Don't you know there is such a thing as government relief?"

Look," I said, trying to keep my voice even. "I depend upon someone a little higher up than the government. I've asked my friends not to vote for me. I don't want to leave home. If I'm elected, it won't be because I wanted to be, but because of someone who knows better than I what is best." I'm sick, sick, sick of people trying to push me off onto public welfare.

I voted for myself so my record would look less embarrassing, then went home to make a tub of soap. I like to make soap. It soothes the nerves.

November 8. We went to Gordon Clark's home in St. George to keep an all night wake with the rest of the Republican candidates to listen to the election returns. It was beastly tiring, in a fun sort of way. By 2:00 a.m. the courthouse quit taking calls. Gordon Clark lost by 100 votes. I won over Mrs. Morris by 190 votes. The radio this morning said Mrs. Morris got 1630 votes and was unopposed. The folks in this end of the county felt bad because they wanted me to win.

All day I supposed last night's figures were a mistake, that Mrs. Morris had won. This afternoon, Sheriff Prince came to congratulate me, and to tell me they were waiting with open arms for me at the courthouse. And I just stood there, stirring soap in the black tub. My soap making duds, and dirty hands did something to his enthusiasm. He expected to find me jubilant. Instead, to hide my embarrasment, I stooped over Lolene and wiped her runny nose, and he kind of eased out of the place, saying some toneless little speech about always admiring me, and being happy for me.

After he'd gone, realization hit me. Yikes!!! What am I going to do? Just what am I going to do?

November 15. Terry came in from school with a boom, boom, boom. That's his natural speaking voice.

"Terry," I shouted, trying to be heard, "there isn't another person in the world who talks as loud as you do."

"Ohhhhhhh yes there is, Mother," he grinned, making half-moons of his eyes.

"Who?" I demanded.

"That old Mrs. Blank that lives across the street from kindergarten. I went by her place and picked a flower that was sticking through her fence. Her window opened and she stuck her head out and yelled, 'YOU BRING THAT 273273 FLOWER IN HERE RIGHT THIS MINUTE.' And so I picked them all and took them in.

"What kind of flowers were they?" I asked.

With a puzzled frown he said, "I don't know. They had a black bottom, and a blue top and green petals."

"Why didn't you bring one home?" Shirley giggled.

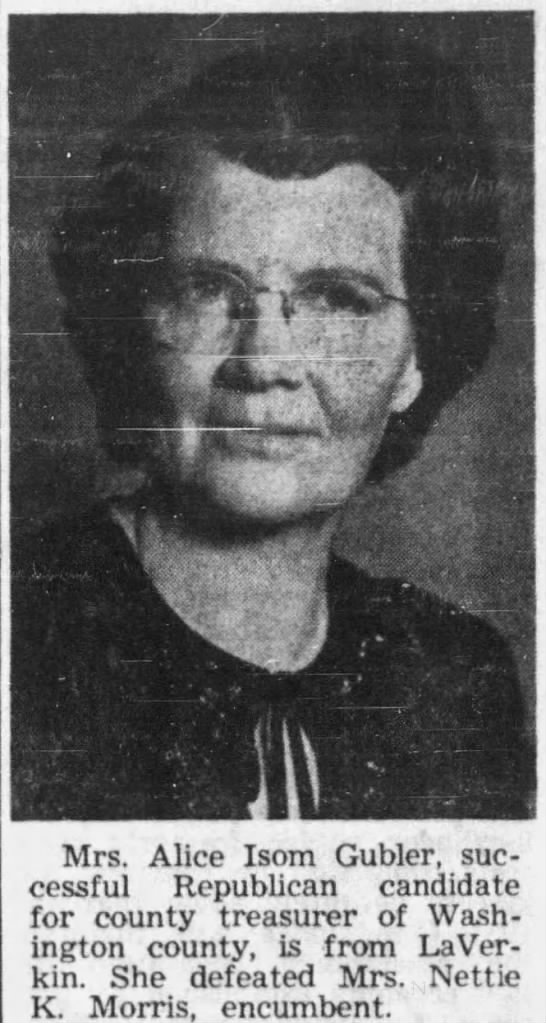

From the Thursday, 09 November 1950 edition of

Washington County News (page 9)

Mrs. Alice Isom Gubler defeats Mrs. Nettie K. Morris (encumbant) for County Treasurer

"How could I?" His chest began to swell, and so did his story. "It was too big."

"You could have brought it on the bus," Shirley suggested.

"I could not. The bus doors are too little to get even one flower through."

"Then how did you get it in the lady's house?" Shirley asked.

"Silly. Her house has two doors like a church house, and when she saw me coming, she opened both doors wide so I could get it in."

"But you said you took them all in," Shirley said.

He grinned. "I was just thinking they were bigger than her doors, but they were only this size," making a circle with his arms about the size of a milk pan. Seeing the stern look on my face, he said in a small voice, "Well, really it was only this size." He made a two-inch circle with his fingers.

November 17. Everyone wants to know how I'm going to manage my home, my family and my new job. And so do I. I don't have a car. People think Oscar Barrick, the County Clerk, should take me back and forth. He doesn't relish the idea. His wife says, "Why don't you sell out and move to St. George:" That suggestion keeps popping up. I love our home. Today I Kemtoned the living room, washed the windows and brought in new houseplants from the nursery. I don't want to leave this place. What comes next?

Kem-Tone paint ad circa 1951