(1960)

379379 January 1. I'm trying to clear away enough of the past to make room for the New Year. Here's a note from Fergie which says, "I drove up to Kolob all by myself just to watch your brother Clinton do some cat work. He is the sweetest man in the world." Yes, Fergie, I agree that at least he is one of the sweetest.

I remember the day after New Years four years ago when I went with Clinton up on Coal Pitts to brand a calf. He built a fire of cedar boughs by a big boulder to heat his branding iron. The day was as cold as a January day could be, so I climbed upon the boulder above the fire. The wind was austy. Clinton shouted at me to move just as a gust of wind whipped the fire over the rock. Flames enveloped me. I leaped down on the opposite side and flung my coat over my head, because I could hear my hair and my eyebrows frying. My eyelashes were melted to beaded blobs that locked every time I blinked my eyes, and my eyebrows crumbled and fell off when I rubbed across them. For a few weeks I had to curl my hair different to hide the bareness around my face. My face was tender for a few days too. But I liked going with Clinton so much. He has been a dear brother to me, and a thoughtful, kind, good uncle to all of my children, taking them with him as often as possible.

March 28. Norman and Ann have a brand new little son born this day. Kathleen has a baby brother. (Lloyd).

April 15. Ah such luxury. Here I am lounging in a heap of pillows on the cot under the honey locust tree. The tree, sweet with yellow flowers and tender green leaves , is swarming with bees. The sky, the 380380 clouds , the sun, the breeze, the hum of the bees, the chirp of the robin—this is happiness. My cup runneth over. I am privileged to enjoy this day because of the fine group insurance Coleman Engineering has. I'm home from the Dixie Hospital convalescing after a hysterectomy.

Helen Bleak came in the same time I did for the same thing. We were mighty tickled to be with each other. Charles Pickett, the County Attorney, brought orchids to both of us. Just imagine! Each of us got a big orchid in a vase!

Bill Sanders, Carl Staheli, Wendell Hall and my brother Clinton came to my room and sang one quartet after another as I lay misty-eyed on my pillow.

A nurse came to the door and said, "Would you folks please come into the hall and sing:.' Patients are standing by their doors the full length of the hospital."

So they did. After they left, that same nurse came to my room. "Those men will never know how much good they did," she said. "There's an old man across the hall who has not responded to a thing for days. When I went into his room just now he smiled and said, 'I heard the most beautiful music.'"

September 17. Terry hasn't missed a day in the past month without saying, "Jay Frazer will sell me a horse for $30, and give me until spring to pay."

He's like Lolene was about a tether ball. Every meal she'd say, "I can hardly eat for thinking about a tether ball." Then she'd awake in the mornings she'd say, "I dreamed I had a tether ball." That went on until Christmas, when she got her tether ball. But Terry isn't going to get a horse for Christmas. Horses eat.

Sunday a red pickup drove into our yard.

"Mother," Lolene whispered, "that's Jay Frazer and I think he has a horse in his pickup."

Terry bolted out the door. Peering out, all I could see in the pickup was an oil drum.

"Mother, come and look," Terry shouted.

Jay was poking at something in the pickup bed. Embarrassed he said, "I can't make it stand up."

Pretty soon it did. There before my eyes was the littlest midget that I've ever seen that could be called a horse.

"It's a mustang," Jay said.

It was all ears and nose. It head was as big as a full grown horse, but it scarcely had a body. It wasn't even leggy. I looked at Terry. Written on his face was adoration and longing. I knew I had but two choices. One was to let Jay unload the critter, and the other was to plan Terry's funeral if I didn't. The horse stayed.

Last night when Richard Beaumont came for Terry to go home teaching, Terry led his little quadruped out for him to see. The family clustered around to pet the little critter. Richard poked him in the ribs.

"Hey, don't," Terry protested.

381381 "How do you make him kick?" Richard asked.

At that moment the little mustang swung a hind leg sidewise and whammed Richard full on the shins. The horse didn't bat an eye or turn his head, but looking straight ahead he had landed the blow accurately. We cracked up laughing.

Grandpa Gubler came to see what we had. Terry had been scrounging rings and leather straps from Grandpa to make a bridle. When Grandpa saw the animal he laughed and laughed. Finally he said, "That horse is stunted. It will never grow. Terry will be an old man before that horse is big enough to ride."

When Ward Wright saw him tied to the pecan tree he shouted, "Alice, it's dangerous to leave that horse tied to that tree!"

"Why?" I asked.

"Because if he runs out to the end of the rope he'll uproot the tree."

September 28. Shirley phoned me at the office. "Mother, what shall I do? Two horses are pacing up and down in Ann's garden mashing everything. Ann is going to be sick when she comes home." (Norman and Ann are living on the bottom of the lot in a trailer house).

"Find someone to help you."

The little horse had whinnied until he attracted a couply of strays. They climbed over the boards and tin roofing at the back of the old house, trying to get into the corral. Ovando came to the rescue and let the fence down around the garden so the horses could get out. He said one horse reached over the fence, getting close enough to the mustang to bite him.

This evening Gordon said, "Terry's mustang was caught from a band of wild horses in Hurricane Valley. Grandpa says he wouldn't give 30¢ for him, let alone $30.00."

"Oh well," I said, "Terry isn't really going to buy him. He's smart enough to know the little fellow will never be a riding horse."

Terry gave me a grateful look. "I guess I'd better call Jay and tell him to come and pick up his mustang," he said.

September 29. Shirley loves Perry Houston from Mesquite. Perry went to college at Cedar City while Shirley was at Dixie, so maybe she's right about the CSU boys being the cutest.

Shirley spent her summer earnings from Vonda's Cafe on a Singer sewing machine—$488.00—all paid for. Besides paying $100 rent, she still came off with money for clothes. Not bad at all.

But oh, that sewing machine! It stands in the splendor of its newness in our living room, and we give it a wide berth, neither touching it nor breathing on it. But that's ok. Shirley sews cleverly and creates beautiful things on it. Now she has registered for the fall quarter at Dixie and is living with the Harrisons.

Helen and DeMar were married on the 24th of September. DeMar retired early the night before the wedding. I went to his room at 8:30 and found him sound asleep. When I spoke, I got no response. Shaking him, I got only a grunt. The next morning he was up and ready to ao to the temple 382382 by 6:30.

"How in the world did you get to sleep so fast last night?" I asked. "I got so tired of tossing and thinking last night that I wet a handkerchief with some of the choloroform from my chemistry set and inhaled it," he replied.

The wedding was lovely, temple ceremony, reception and all. Theirs was the traditional wedding dance with a live orchestra and a program. At Helen's request, DeMar strummed his guitar and sang, "Have I Told You Lately That I Love You." Now he's driving truck for Serret at Cedar City, so that's where they're planning to live.

I had the happiest feeling as I folded Lloyd's nightgowns from off the line today. It set me thinking of the little guy who wears them. Norman's and Ann's six month old son is a darling. Kathie loves her little brother, and talks so cute to him. Grandchildren are grand!

Shirley tints photographs at Durante's studio after school. She's doing twenty-five pictures of Val Jennings who corresponds with twenty-five girls, names he got from a magazine. When a picture of a cute little girl, or baby comes in to the studio, Shirley sandwiches it in for a change. Val walks from Hurricane to St. George to pay the studio $1.00 a week on his pictures and reports on his progress with the girls.

October 3. Lolene is sorry she applied for a job at the school lunch room, because she got it. She sprays dishes. They tell her they will let her take turns serving. She will like that.

This evening Lolene was doing the splits on the back porch. One foot was propped up on the bathroom window sill.

"What on earth are you doing?" I asked.

"I'm acting like a teenager. I read all about it in a book, and know how they act. The book says I've a right to a normal adolescense."

We're running out of contracts for tests on the Mesa. Things are so slow that we're urged to do our best to look busy.

October 12. Terry is in the limelight again. I just got to work when Shirley phoned. "Mother, Terry has shot himself."

Shocked, I asked, "Is it bad?"

"Yes," she replied, "can't you hear him?"

I went sick all over at the sounds of his agonized groaning. "I'll be right down." Turning to Dorothy I said, "I've got to go. Terry has had an accident."

She called Steve's office. By the time I got to the front door, Harlan James was out in front with the boss's car. We fairly flew down the hill. I didn't know what to expect. I wondered if Shirley could administer first aid to keep him alive until we got there. And then a calm, peaceful feeling came over me, and I knew Terry would be all right.

We found Terry sitting by the kitchen table, ashen white, his eyes a little glazed. He had one boot off, and there was a purple, swollen toe oozing blood onto the floor. The boot had a hole in the middle of it. 383383 Shirley thought he had shot through the-middle of his foot, but the boot was inches too long for Terry's foot, so actually he got it at the base of the second toe on his right foot.

We loaded him in the back seat of the car with pillows under his foot and headed for the hospital.

Terry had been shooting sparrows out of the bamboo with his 22. He rested the muzzle end of the gun on his shoe and cocked it. When he raised it, it blasted birdshot into his foot. The bone of that toe was shattered. By the time we got him to St. George his foot had gone numb, and they didn't have to give him a shot before operating.

The doctor took all kinds of litter out of his foot. There was packing that was in the shell, a bit of leather, a bit of sock and pieces of lead. He opened the hole wide and threaded a strip of rubber through it like you would thread a needle, This was to keep it open so the lead could sluff away. Terry didn't feel a thing. This is his fourth day in the hospital and they still have the rubber in his foot. I don't know whether he will keep his toe or not. So there goes the jitter-bug class he was enthused about starting this week.

October 15. Terry is home from the hospital. Shirley says she's going to shoot his other toe so he'll have to go back. Home was peaceful while he was gone.

He has captured a couple of blue jays already since he came home. Yet he is supposed to keep off his foot. He's going to build a cage for them and raise tame ones. Trouble is, both of his birds are flashy males. Gordon has one special thing that is different from his brothers. He likes school. Especially chemistry, seminary and chorus. Mr. Larsen, the new music teacher, is impressed with Gordon's voice, so he is giving him free voice lessons. Walter Segler has started up his molasses mill. Last fall, every time I wondered where Gordon was, I found him at the mill. This year he is working there on Saturdays and after school.

The only girls Gordon is interested in are the ones that Terry discovers first. When Ann's sister Irene went to school in Hurricane, Terry and Gordon constantly competed for her attention. When the family went swimming, Gordon kept dragging Mary Tally's niece into the deep water, leaving her stranded on an inner tube, just to see Terry be the big hero and rescue her. When Terry walks a girl home from NIA, Gordon walks the same girl home the following week.

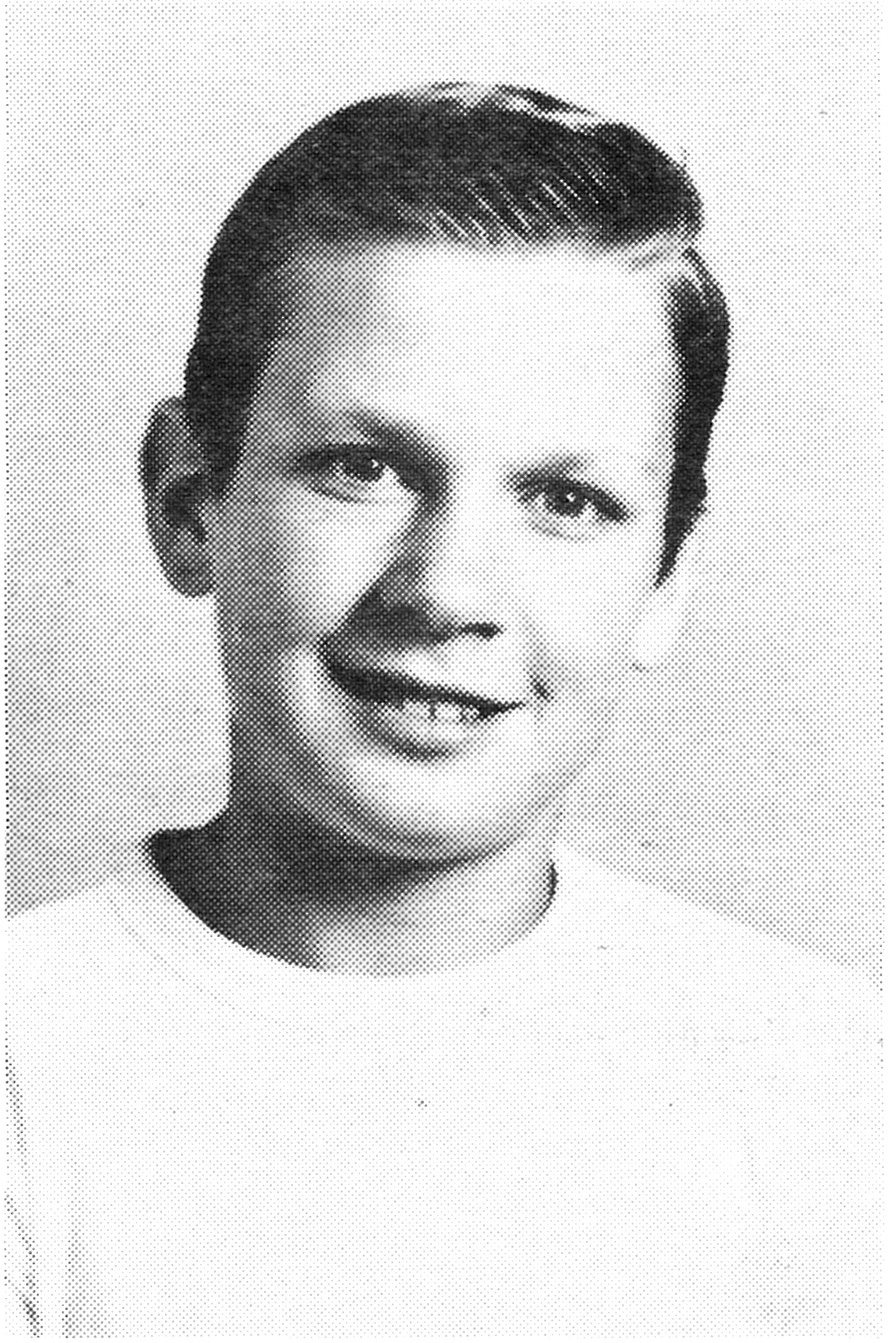

November 1. Grief is our companion once more. Gordon has been taken from us. He spent his last day at home with me. It was Saturday, and Terry had gone to LasVegas with Marilyn. Gordon and I spent the day cleaning the yards.

"There's something strange about this day," he said. "I can't decide what it is."

Often he gazed across the fields, or sat on a bench looking at the ground pensively.

"Oh come on, snap out of it," I said.

"But mother, I have the strangest feeling about today," he said.

384384 He had been testing the sights of a pistol.

"I wish you'd put that thing away," I remonstrated.

"There's something wrong with it," he replied. "The sights aren't true."

Just before sundown, DeMar drove up. "Gordon, let's go over in the foothills for a little while and look around."

Gordon brightened. "I guess that's what's different about today. Everyone is deer hunting but me." Running for the car, he called back, "I'll see you in a little while, Mother."

A little while? How long, oh how long is a little while? Within half an hour my telephone rang.

"There has been an accident," Lucille Fish said. She told me where to find my boys, and offered me her help.

Who was hurt, or how badly, I did not know. "Oh, Heavenly Father," I prayed, "Please don't let DeMar or Gordon be maimed or crippled for life!"

I phoned Helen's parents, Isabel and Ermal Stratton, then ran to the highway to meet them.

A crowd had gathered by the side of the highway beyond Pintura, and I was told that the younger of my two boys was up in the foothills dead. He had been testing the sights of a pistol. When he looked down the barrel, the gun went off, hitting him between the eyes. A numbness went over me.

"The older boy is crying hysterically by the side of his brother," someone said.

My mind took wings through the dark cedars to my sons, but my feet slowly turned to the car. Alone I sat in the back seat, my head in my hands. Why didn't I climb the hill to DeMar and Gordon? Something restrained me.

Darkness was filling the ravines, still I was aware of a strange burst of light. How can such intense grief and pain be associated with light? A sweet something whispered peace. Peace? Oh my weeping heart! Through the fragments of broken thoughts, one thing came to me clearly. For eleven years I had had our seven youngsters to myself, and now Winferd needed one of them. This thought took the despair out of my grief. Grief can be borne when there is the light of hope at the other end of the road.

Gordon's accident was on the evening of October 22. Isabel was by my side through all of the final arrangements. She became especially dear to me. My family and Winferd's family, our neighbors and friends surrounded us, and our home was filled with love. And Gordon! Gordon, dressed in his beautiful white suit—Gordon, so handsome and tall—six-foot, two! Oh, Gordon, Gordon—goodbye my son. I shall not lose sight of the light of hope.

My week at home writing thank-you cards is over. I am back on the job on the mesa.

385385 Mark Johnson from Holden wrote: "Victory over bereavement comes easier if you will deliberately reenter the field of activity. …by quiet acquiescence, and by deep and undying faith in God. …your good and handsome son tonight is with his own father, and I am most sure that their happiness far surpasses any that you have ever known."

From Bloomington, Indiana, Donworth wrote: "And now it is Winferd's turn to revise his image of his son who was so small when they parted— I say he will revise his because I find it difficult to believe that our loved ones see us any more than we see them. If they were able to see us in our daily activity, they would become so absorbed in what we were doing. …so filled with concern for our mistakes. …that they would not be constructive, productive members of God's heaven. So now, in my imagination I see Winferd showing Gordon about his new surroundings, proudly introducing him to all of his friends and saying, 'Do you see! What I have been telling you about my fine family is true. This one is taller and straighter and finer than even I had imagined.' And he'll feast his eyes on his son with whom he was permitted so little time before, and will say to himself, 'I hope Alice and the other children won't mind too much losing their son and brother. It is so good to have him here—to not be alone anymore.' In no time at all he'll have him enrolled in a heavenly school with others of his age so that he can be developed with all speed in his understanding and love of the Gospel that he may go about the urgent duty of proclaiming the Gospel to the millions who daily die without having heard it.

"Make no mistake, Gordon, young and unexperienced as he is, is far ahead of the great multitudes of his fellows who daily make the transition from earthly to heavenly existence. He will rapidly adjust to the new existence and be grateful to finally make the acquaintence of his wonderful dad. Won't they make a wonderful missionary pair?"

LaRett Stratton wrote: "Be glad that God trusts you with some problem. Thank Him for the compliment. He believes you have what it takes to handle them."

November 10. When I talked to President Snow at the temple, he said, "Come and get your son's endowment work done immediately. He needs the Melchizedek Priesthood so he can go with his father to preach the gospel."

Last night, DeMar did Gordon's temple work, and I did Jaunita Fergerson's (Fergie).

It was only a month ago when Gordon presented me with the seminary text, "The Restored Church" by William E. Barrett. "I didn't have to buy this book," he said. "The seminary would let me use one of theirs, but I thought you would like to read this."

Then he talked about preparing to go on a mission. "How will we be able to finance my mission?" he asked.

"Don't worry about that," I replied. "We've got two years to prepare. We'll finance it all right."

Two years? His call came early. He has the Melchizedek Priesthood now. He can go full speed ahead. And little Fergie! When I think how happy she is to have her temple work done I can still feel her arms around me and her wet tears on my cheek.

386386 December 8. Last weekend, when Shirley was home from school, she used dry-cleaning fluid to wash her slacks. She got the bright idea of pressing them dry.

"Look at this pretty white cloud," she said to me as she ran the hot iron back and forth.

Like an explosion, flames burst forth. She grabbed a blanket to smother the fire. Black smoke filled the room, banking thick against the ceiling, almost suffocating us. Shirley's slacks, the ironing board cover and pad drizzled puddles of fire onto the floor, burning patches through the floor covering. Soot blackened the walls and curtains, which resembled the pile of velvet. We moved my bed out onto the back porch, where I've been sleeping all week.

Sleeping outside in December isn't bad. I had layers of paper under the matress, and in between the blankets over me. Getting in and out of bed was the cold part. We've spent all of our evenings re-papering and painting the walls and woodwork, and have put down a new floor covering.