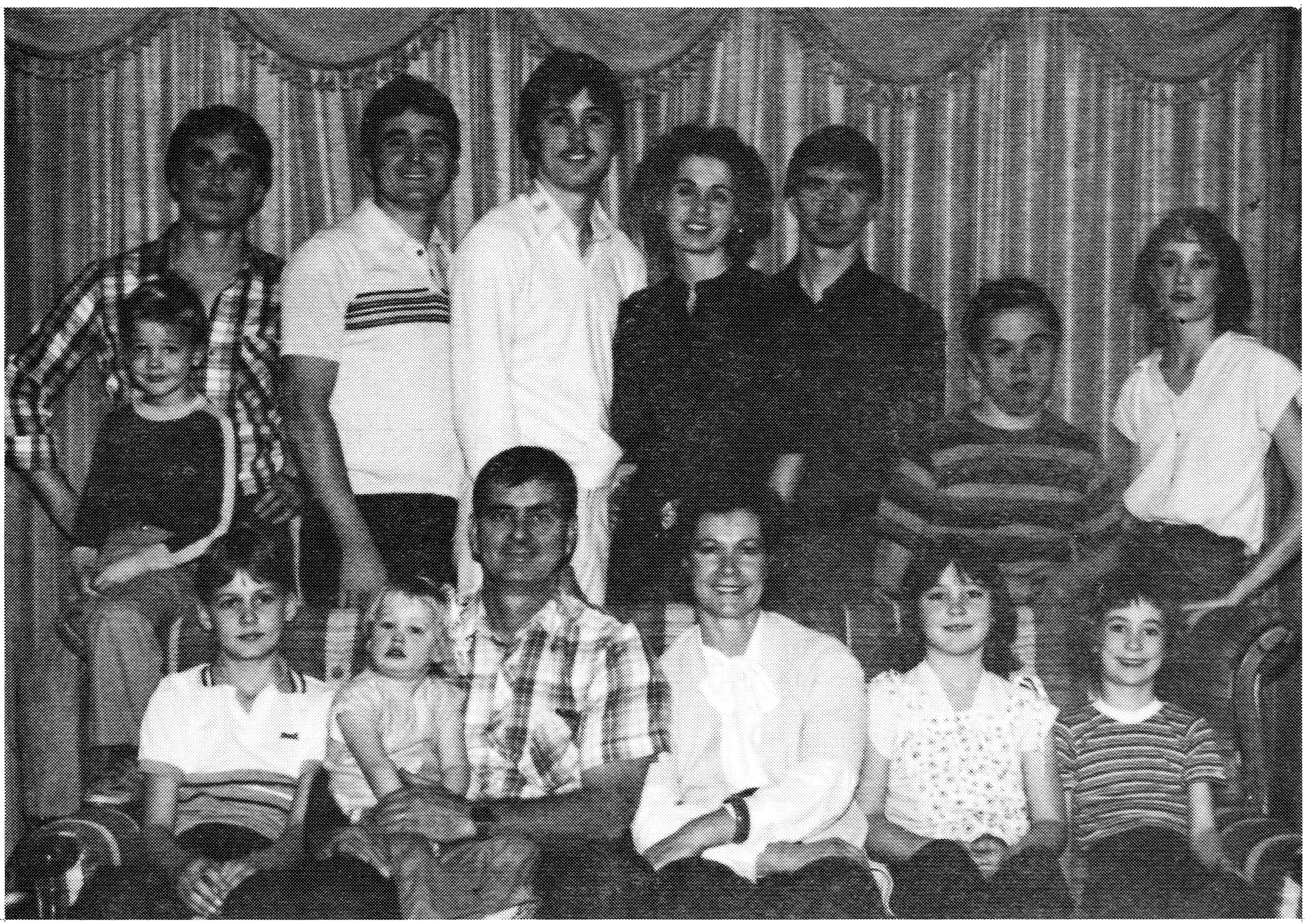

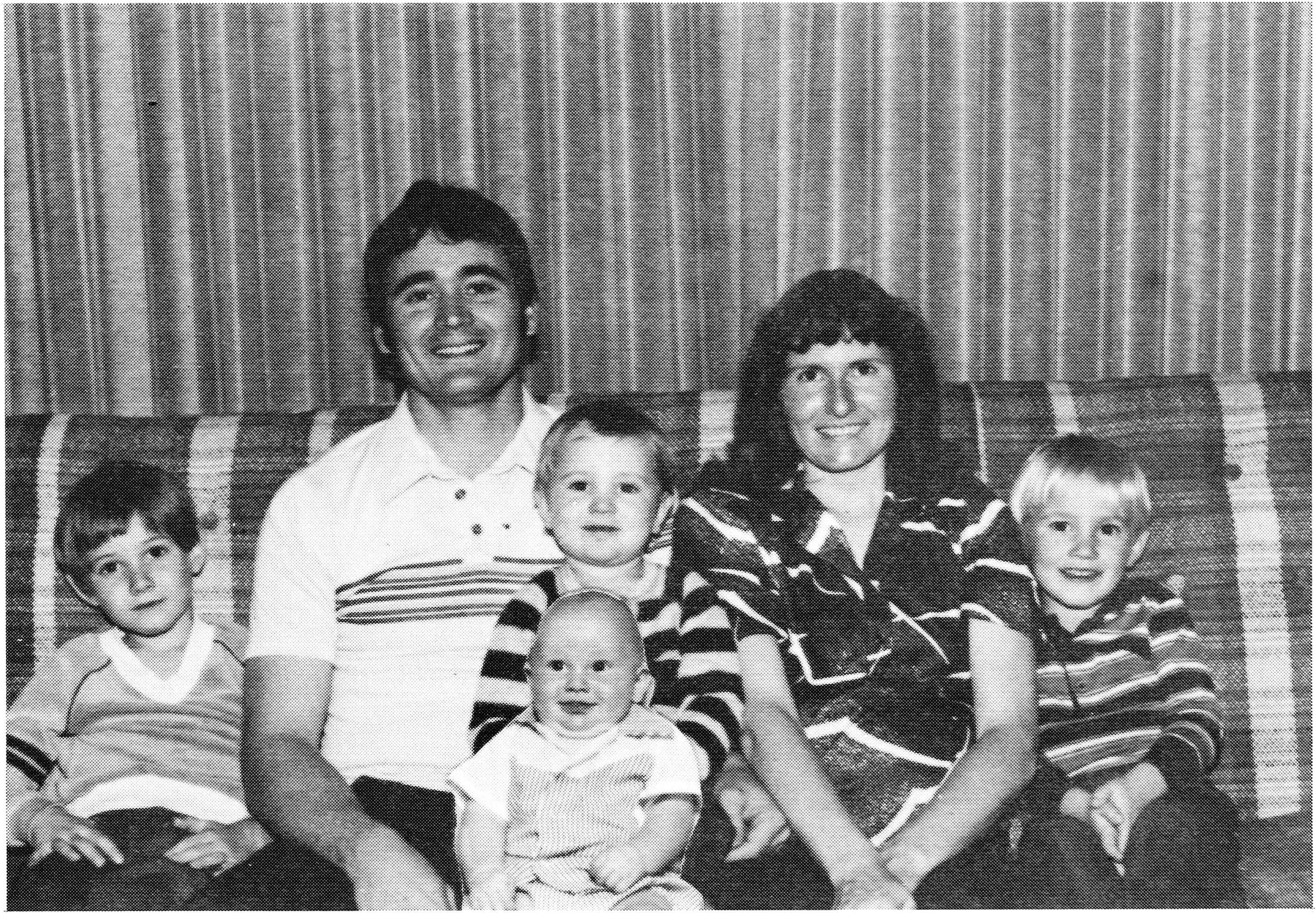

DedicationDedication Volume I & II of my life's story, "Look to the Stars," is affectionately dedicated to my children. They are the golden link between the rich heritage of my past, and the bright hope of the future. My love for them is boundless. May they always see the beauties of this creation, and may their rejoicing ascend to Heaven.

Copyright © 1983-1985 Alice Isom Gubler Stratton

All Rights Reserved.

Web adapatation Copyright © 2010-2018 Trustees of Alice Isom Gubler Stratton

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the author or her trustees.

Intro 1Intro 1 The little barefoot boy pattered down the street in Rockville. There on the sidewalk was a nickel. Excitedly he picked it up. Further on he found a dime, and then another. Holding the coins in his hand he marveled. Such a lot of money! Walking ahead of him was a stranger.

"Hey mister," the boy called, racing to catch him. The man turned as the boy thrust the coins at him. "Do you have a hole in you pocket? I found these on the sidewalk behind you."

The man put his hand in his pocket. Sure enough there was a hole. Scrutinizing the lad, the man asked, "Are you William Robinson CrawfordWilliam Crawford's little boy?"

"No. I am

"I thought you must be

And that's the kind of people my forebears were. They recognized the truth when they heard it, and accepted the gospel. My great-great grandfather

TO THE MEMBERS OF THE GIFFORD FAMILY

Dear Friends:

As one who is very grateful, may I express the gratitude of the Kimball family that your ancestor, Alpheus Gifford, was so responsible for bringing our ancestor into the Church.

I believe in family reunions and believe that much good can be accomplished by the association of family members to recount the stories of the family and keep them fresh in the memory of the people of the family.

I hope also that the members of your family will keep records of their own lives and the lives of their family members. Such biographies and autobiographies become very precious as time goes on and generations succeed each other.

Please accept my best wishes, and may I express appreciation for the other members of the Kimball family and also for the Church for your faithfulness and devotion and loyalty.

With kindest wishes,

Faithfully yours,

Spencer W. Kimball

President

Intro 2Intro 2

Great-grandfather

Our people came from England, Canada, New York and Illinois, joining the pioneer trek to the Great Salt Lake Valley. From there, Brigham Young sent them on to colonize towns further south. They lived in dugouts and wagon boxes, and ate pigweeds, cane seed and wild berries at first. They became bishops, patriarchs and auxiliary heads in their wards, part of them living in the United Order.

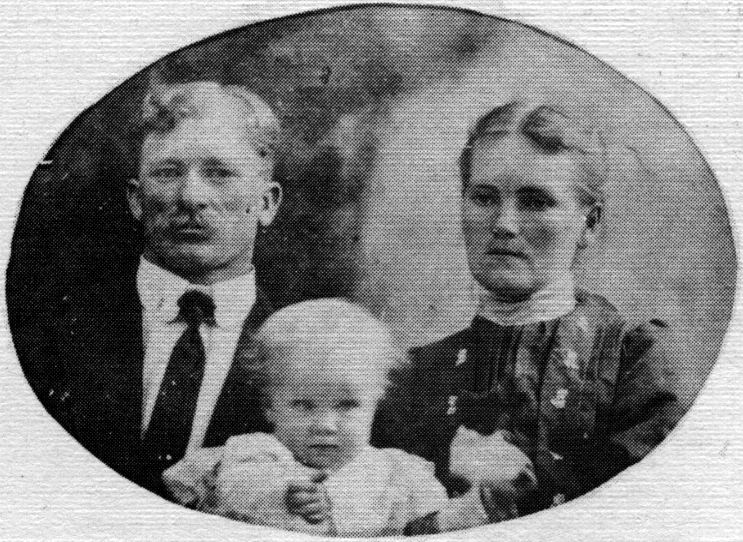

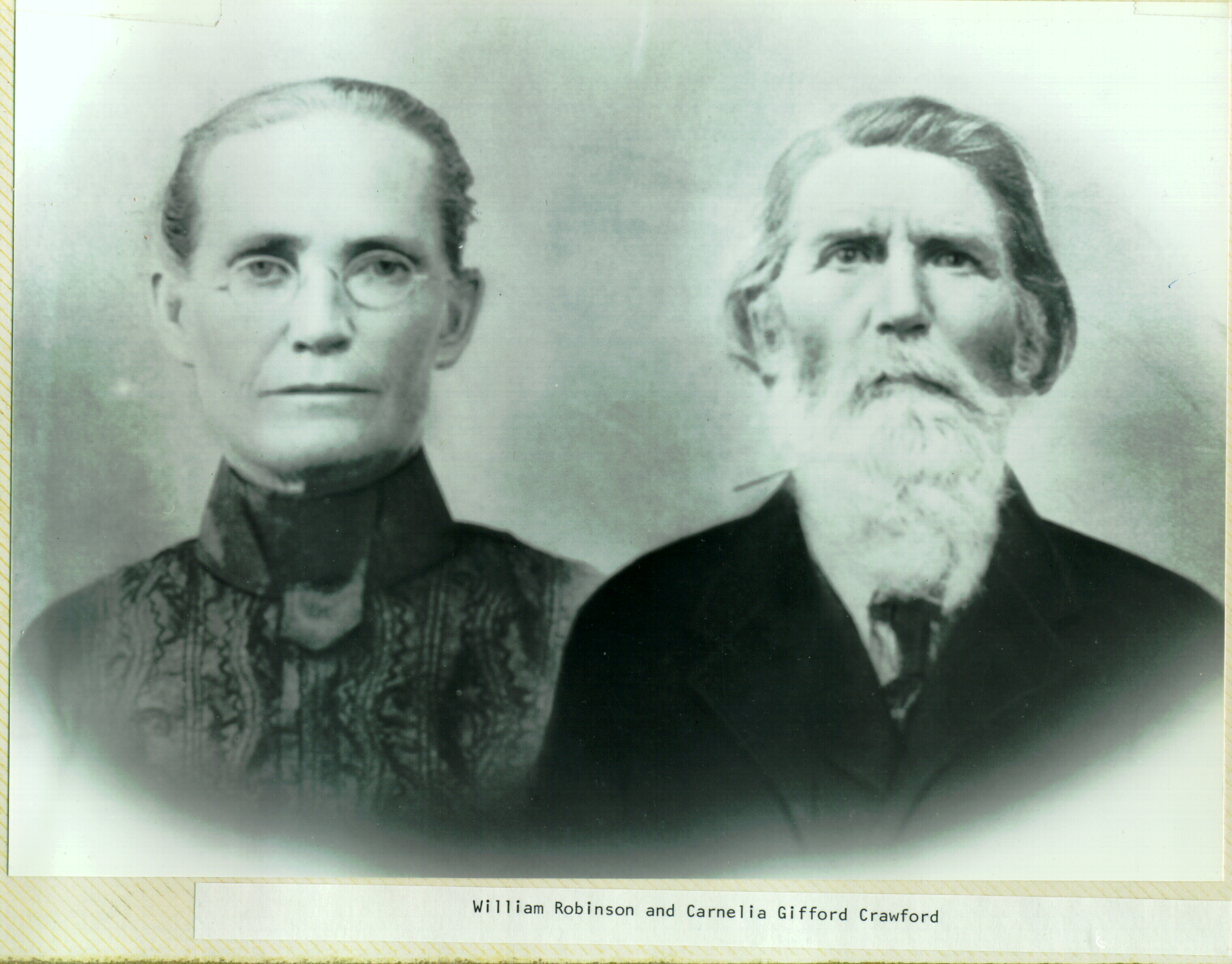

Our father, George Isom, grew up in Virgin, Utah, going on horseback up the river to Oak Creek selling encyclopedia sets. That's where he met our mother, Annie Crawford, the sixth child of William and Carnelia Crawford's family of thirteen children.

According to Aunt Fanny, Papa had to court Mama in the living room where the family was. Fanny was mischievous. She hid behind the kitchen door, where Papa attempted to kiss Mama goodnight. She poked a comb through the crack just before their lips met, and they kissed the comb.

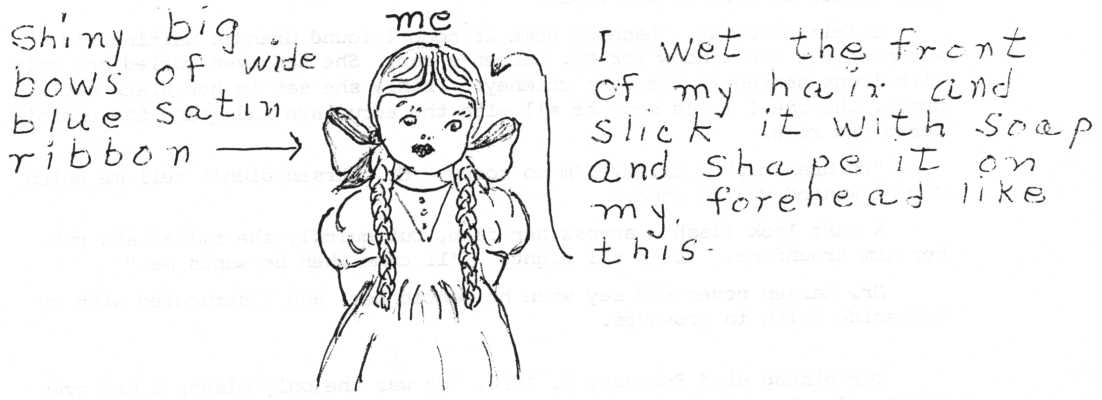

AKAK I express my appreciation to my daughter Lolene Gifford for the many hours of proofreading and careful checking of my manuscript, and to my granddaughter Laura Gubler, who came as a lifesaver at the conclusion of the book to do the technical job of indexing, and to my granddaughter Marie Gubler who read for me when eye troubles beset me. Special thanks goes to my husband Ermal, whose patience was tried to the limit with my endless typing, but who endured with good humor. I appreciate my children and grand children who have cheered me on, encouraging me to finish this work. I appreciate my sisters who have helped recall the scenes of my childhood, especially Kate for her work of art in illustrating the place where I was born.

The digital version of this book was created posthumously, after Alice's passing in 2000. The following made significant contributions to bringing Alice's book to the digital realm:

- Kendall P. Gifford—Grandson of Alice—bulk scanning of the original book, conversion to text, formatting, editing

- Aaron D. Gifford—Grandson of Alice—some scanning, conversion to text, formatting, editing, web hosting

- Andrew G. Gifford—Grandson of Alice—conversion electronic format

- Lolene G. Gifford—Daughter of Alice—conversion to electronic format

Online Scanned Pages:

The entire book, complete, can be read online, by viewing scanned images of typewritten pages. All pages were scanned by grandson Kendall Gifford and are available online here:

The Entire Book:

You can read or print the entire book (except for INCOMPLETE) sections all at once by visiting the following web link:

https://www.aarongifford.com/alice/looktothestars/complete.html

The Entire Book (scans of the typewritten book):

WARNING: This is a VERY LARGE download, about 2.7 gigabytes. It contains scanned images of every page of the original typewritten book.

https://www.aarongifford.com/alice/looktothestars/Lool%20to%20the%20Stars%20by%20Alice%20Isom%20Gubler%20Stratton%20(HiRes%20Scan).pdf

33 While I was still in Heaven, my cousins Iantha and Ianthus Campbell were born. Aunt Mary and Uncle Lew already had five girls and Iantha made six. But Ianthus was a boy! It's easy to guess how tickled Uncle Lew was about that. The twins arrived on August 10, 1909.

Mama and Papa had had four little girls, but my sister Josephine only stayed a little while, then returned to Heaven. That left Annie, who was six and one-half, Kate, not quite five, and the toddler, baby Mildred. Annie decided to ask the Heavenly Father to send twins to our family too. Kate also prayed for twins for awhile, then she decided Mama had enough girls, so she just asked for a little brother. Annie persisted in asking for twins. For eleven months she prayed. She has written:

Finally our prayers were answered! One night in mid July of 1910 when we went to bed, we said our prayers as usual, and when we awoke in the morning, the miracle had happened! Grandma was holding a tiny baby boy in her arms and there in the bed with my mother was a tiny baby girl. How wonderful! Words cannot express our joy. The Lord had answered our prayers by sending the desire of our hearts. Twins! We named them George and Alice for our grandparents. How we loved them!1

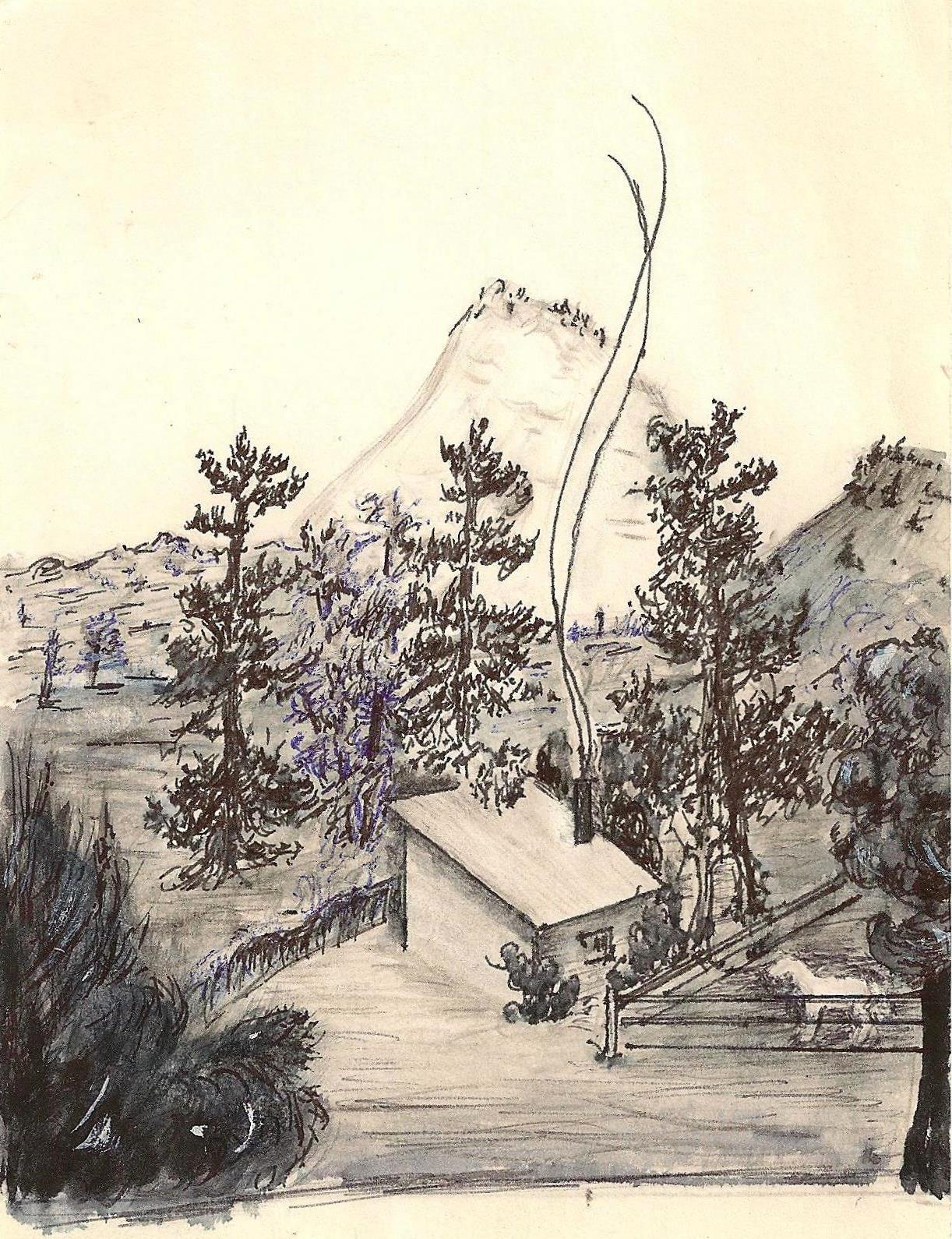

[Lower Kolob area, now a part of Zion National Park, Utah]

We arrived on July 17, 1910, on Aunt Ellen Spendlove's birthday, and on the anniversary of the landing of Noah's ark. (Genesis 8:4) We were born in a little lumber shack at the sawmill on Kolob. Grandma Isom was the doctor and the nurse.

According to an old Chinese tradition, if the first food a child ever tasted was baked apple, the child would become a fine singer. So Grandma baked an apple and scraped a little of it onto each of our tongues. I have no idea what my voice would have sounded like if it hadn't been for that.

My parents had been homesteading on Kolob since 1908, returning to Virgin in the winter time. Recorded in Mama's Memoirs is the following:

In 1911 we closed up the old home at Virgin and came direct from the mountain to Hurricane, where we had built a 12 X 14 granary but the babies took sick and being so cold and crowded, Alice and William Spendlove took us to their home where we could give them better care. … A week after we moved to Spendlove's, George died of inflammation of the bowels and was buried amid one of the most terrible north winds we have known. It was too severe for anyone to go to the graveyard except those that did the burying.

The Hurricane Canal froze over. Water, running over the ice, spilled down the banks, glazing the streets. Mama stayed with me, for I was not expected to live. My sisters wept. Annie remembers lying on the family bedrolls in Aunt Alice's living room, crying bitterly. She could not be comforted. Papa's heartbreak must have been great.

Is it possible that I remember my twin brother? It seems like I do. In my mind is a picture of another baby sitting with me on Papa's lap, while he sang a happy, nonsensical thing like "A chicken went to bed with the whooping cough." We both wore little white dresses. I have had an awareness of my brother George throughout my life, and I have grown to love him dearly.

44 The first five years of my life were my dominant ones. Kolob was Heaven to me. As soon as my sisters were out of school each spring we prepared to return to the ranch. The bustling of cooking and packing was a joyous time to me. I was surprised to learn years later, that the business of moving a family back and forth was just plain hard work for Mama.

We always camped at Sanders's Ranch on our way and one of Uncle Ren Spendlove's boys, either Whit, Ianthus or Cliff came along to help with the team. I loved camping out. I reveled in the smell and the squeak of harness leather and the clinking of buckles and the sounds of the wagon as it sighed and relaxed, cooling off in the night. Stretched out on the family bed spread on the ground, I listened to the horses munching grain in their nose bags, the gentle crackle of the dying campfire, and the stars, the millions of singing stars!

"Mama," I asked, "are all of the stars whirling? Is that what makes them sing?"

Mama listened thoughtfully, then she said, "No, the music you hear is made by the crickets and katydids and night birds in the bushes and trees, and by the water in the creek tumbling over pebbles."

I listened again and realized that the chirping and twittering and gurgling really was ascending up to instead of down from the stars.

Carlyle once said, "Give us, O give us the man who sings at his work. … The very stars are said to make harmony as they revolve in their spheres." The Prophet Job was informed that while the foundations of this earth were being laid "the morning stars sang together." Job 38:7

Well, the last morning star had scarcely faded when we broke camp and were on our way again. We had a long hill to climb before the sun got too hot for the horses. At Lamb Springs we ate breakfast and let the horses rest before their long hard pull through the sand.

We had to walk to lighten the load. I bawled because the sand burned my feet, still I pulled my coat around me.

"You're a ridiculous child," Mama remarked.

"But the wind is cold," I complained, then added, "If the trees would stop fanning then the wind could quit."

"The trees don't fan the wind," Mama explained, "the wind fans the trees."

"What a backwards situation," I thought.

With the deep sand behind us, back in the wagon we rode up around the cinder knoll and on past Mulligan's Point, to Maloney's Ranch and then to the Slick Rocks.

The Slick Rocks was the terrible test to the stubbornness of teamsters and the agonizing willingness of horse flesh. We gladly piled out of the wagon here. Vivid in my mind is the picture of Papa slapping the reigns on the horses' backs and yelling, "Git up Mag! Git up Dick!" Iron wagon tires screeched over steep red sandstone, horses strained muscle and sinew, pulling, pulling, leaning forward until they went to their knees. Terrified, I watched. Mag's and Dick's eyes glared wildly, their ears laid back. Sometimes the wagon started to slip back and Papa cracked the whip and yelled louder. The wagon could roll over the ledge on the right and all would be lost. With Papa's yelling and urging, the stout-hearted team made it over the bad spot, where, breathing hard and their hides shining with sweat, they stopped to rest before going on to the summit. The terror was over.

Photo by Aaron D. Gifford, taken spring 2010 near Alice's birthplace

55 We had made our safe return to Paradise, Kolob. My childhood Kolob was bluebells, wild roses and sego lilies. It was sandstone that could be rubbed into the shape of dolls, and pine bark, thick and soft for Cliff Spendlove to carve into toy horses. It was pollywogs in clear pools in the willows and water snakes that left narrow roads through our dugout playhouses in the sand banks. It was games in the twilight, scurrying through the soft sand and across the meadow calling, "barey ain't out today," while imagining the bear was crouching at the edge of the meadow behind the dark trees, ready to pounce upon us as we dashed into the house. It was the smell of pine and sage and oak, the cackle of the sage hen, the flicker of the bluebird and the hammering of the jay. It was the sight of Rube and Jody Maloney's sheep wagon with its bucket of sourdough hanging on the side, dough dripping down the wheels. It was the cheese house, cool and inviting where squirrels played tag through the rafters. It was the little brown wren that nested under the eaves. It was the crack of lightning and the clap of thunder and pine trees falling in a pillar of fire. It was the howl of the coyote. It was water rising in the damp sand where the shovel sought a water hole. It was Old Tiny, the dog, barking down the trail, bringing the last stray calf in at milking time. It was new milk guzzled from a tin cup at the corral gate, making a thick foam mustache across my upper lip. It was tall cool ferns packed around sweet pounds of butter ready to be sent to the store at Virgin. It was hot corn bread drenched with fresh butter at supper time, and the smell of lamp light on an oil cloth covered table. It was little new potatoes scrabbled from under the vine and sweet garden peas and juicy turnips. It was Paradise!

We moved from "Milwaukie," the sawmill canyon, to "Pinevalley", a mile or so on top, but we often hiked back. We would take a picnic and spend the day, where we gathered iron ore rocks eroded in the shape of peanuts, marbles and little dishes.

Elisha Lee's family came to celebrate one 4th of July with us. Papa put the alphogies2 on the saddle horse, with Edith in one leather pouch and I in the other. We rode around the mountain to the ice cave, where he filled the alphogies with ice. Edith and I rode back home in front of and behind the saddle with Papa. Mama made ice cream in gallon buckets that were set inside galvanized water buckets packed with ice and salt. The ice cream was turned back and forth by the bail. Every little while the lid was pried off the gallon bucket and the frozen cream scraped down from the sides with a knife, a drooling operation. There is nothing in all the world that compares with the ambrosia that came from that bucket.

Mama had a special No. 2 tub that she kept sterilized and shining for cheese making. The dairy thermometer, bobbing in the tub full of milk, fascinated me. I watched her stir in the rennet when the temperature was right, and with a long, thin bladed knife, cut the curd as it set, yellow puddles of whey separating as the curds became more solid. Hungrily we hung around. We loved curd, from the first soft white ones to the final squeaky yellow ones after the whey was drained and the coloring and salt added. Probably none of the cheese would have reached the press if Mama had doled out as much of it as we wanted. Still she was generous.

Now a part of Zion National Park, Utah

Photo by Aaron D. Gifford, October 2010

The cheese molds were made of pine slats held together with hoops. The press was a log, outside on the shady side of the house, rigged up for a lever. Mama lined the molds with cheesecloth and the sweet curd was packed inside and put under the press. We were eagerly on hand when she unmolded the cheese, for the pressure had 66 squeezed tantalizing little ruffles of it up around the edges of the mold. Patiently we waited as Mama trimmed these off, for we knew she would divide the .trimmings. among us. Next she rubbed the yellow discs of cheese with butter, smoothing and sealing the goodness in, then set them on the swinging shelf in the cheese house behind our cabin to cure.

Mama sometimes sent me to the sand wash with a little lard bucket to fetch water. We never wore shoes in the summertime and the sand often burned our feet. Once it was so hot that I cried. Mildred took her bucket and ran back and forth to the wash, burning her own bare feet to make a puddle path for me. I carried my bucket of water all the way to the house on the wet patches she had made, while she ran back to refill her bucket.

One sad little task was helping Papa take small animals from his traps while he held the steel jaws open with his foot. His hands were too crippled to set the traps, so that was our job too, while he supervised. I grieved for the woodchucks and gophers and other animals.

Uncle Ren Spendlove's boys took turns helping us. When they came from Hurricane they brought fresh fruit. During those years I never saw fruit that wasn't bruised from a rough wagon ride. I thought peaches and apples had to be bruised to be good. These were squashed, brown, oozy and delicious.

The big pine tree where our chicken coop was anchored was struck by lightening one night, which electrocuted our entire flock of chickens as they slept with their heads under their wings.

The only toys we knew were those we made. Our doll houses were dug into the sand bank with a spoon and decorated with lacy, sweet smelling Jerusalem Oak. The dolls were made of flowers with heads of the shiny black berries from the deadly nightshade. Our wagons were the bleached vertebrae of bones of animals found in the sand. Our miniature world was imaginative and happy.

I was five when the folks stopped going to the ranch. I was the one who closed the gate for the last time behind the wagon. In my hand I had a few tiny new potatoes the size of peas and one little golden cheese that had been pressed in a salt shaker lid. These small rations belonged to my rag doll family. I set them down at the foot of the big yellow pine that the gate was hinged on. After closing the gate, I climbed into the wagon. We were miles down the road before I remembered them. I felt badly. Two years later-when I went to Kolob with Aunt Ellen's family I looked, but there was no sign of them.

That was my last trip to Kolob as a child. All that remained to me were cherished memories. We used to climb the Hurricane hill often, my sisters and I, but we never turned around until we could see the white Kolob peaks and the Steamboat mountain. That was the goal of every hike.

My love for our Heavenly Father began at Kolob. I remember kneeling at Mama's knee as she helped me with my prayer. I felt warm and secure, knowing that even in the dark the Heavenly Father watched over me. This realization took the eeriness out of the shadows that moved outside the tent, and gave understanding to the noises of the night. Pine needles falling on canvas had the same lightness as the scampering of squirrel feet and the occasional thump of a falling cone sounded friendly as it rolled off the tent to the ground.

One day Mama let my sisters and me hike down to the sawmill canyon alone. We became so engrossed in gathering fancy rocks and wild flowers that time slipped away. The sun was settling into the grove to the west as we trudged 77 through sand and sage on the last stretch home.

With our arms full of treasures, we raced to the house to show Mama. The tantalizing smell of hot cornbread greeted us, for it was supper time. But the room was strangely empty. Mama was not there. I shot out the back door. Running to the tent where our beds were, I lifted the flap. The setting sun, filtering through canvas, filled the tent with a golden glow. There, kneeling beside her bed, was Mama. In astonished reverence, I waited.

"What were you doing?" I asked timidly as she arose.

"I was asking the Heavenly Father to bring my little girls safely home," she replied tenderly.

"I didn't know you could ask Him for things in the daytime," I marveled. I had supposed that aside from our regular family prayers, we prayed only before tumbling into our beds.

Sitting on the edge of her bed, Mama drew me to her. "We are our Heavenly Father's children," she said. "He loves us and will listen to us anytime."

It was all so clear. Father really meant father. I was really and truly His little girl, and I could call upon Him whenever I needed to! My heart was jubilant.3

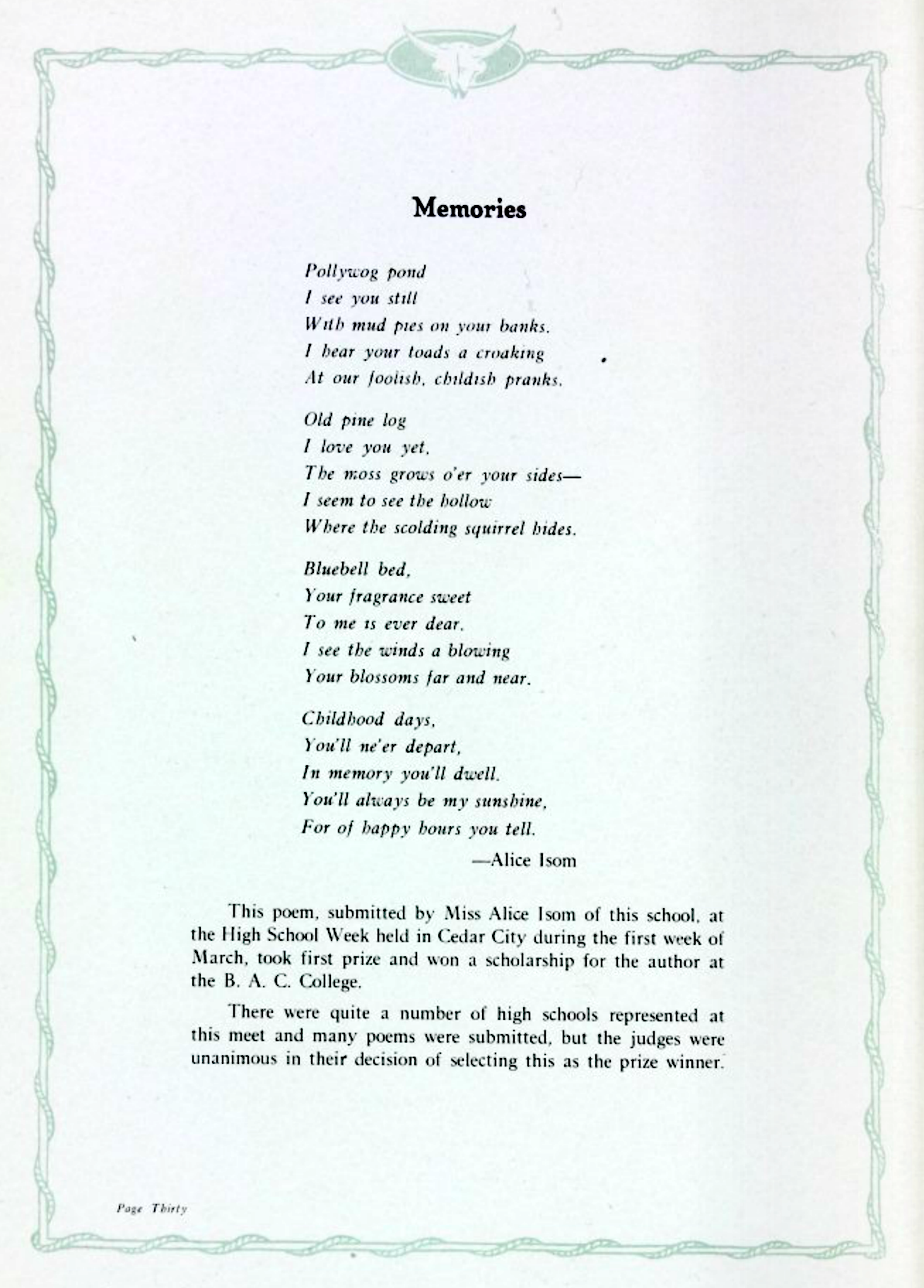

We not only draw spiritual dividends from childhood memories, but other blessings as well. As the composer has said .The song is ended, but the melody lingers on,. so Kolob memories are a melody to me.memories that paid my tuition for my first year in college.

In 1928, my English teacher, Mattie Ruesch, without my knowing it, entered one of my compositions in the lyric poem contest at the B.A.C. On College Day I was awarded the Spilsbury Memorial Scholarship for my—

Memories

Polliwog pond

I see you still

With mud pies on your banks.

I hear the toads a croaking

At our foolish, childish pranks.

Old pine log

I love you yet,

The moss grows o'er your sides—

I seem to see the hollow

Where the scolding squirrel hides.

Bluebell bed,

Your fragrance sweet

To me is ever dear.

I see the wind a blowing

Your blossoms far and near.

Childhood days,

You'll ne'er depart.

In memory you'll dwell.

You'll always be my sunshine,

For of happy hours you tell.

Footnotes

- Story "Double Blessing" published in Friend, May 1978, p. 2.

- Alphogies are leather pouches big enough to hold a child, that hang on each side of a pack horse.

- Story "Home Safe" published in Friend, September 1975, p. 48.

88 Our brick house was built during the sad winter that my little brother died. Mama was tied down with the two of us and couldn't visit the house during construction. Then came the day that Papa took her to see it.

"Welcome to our home, sweetheart," he said as they entered the front door. The winter sun streamed through the windows and the house smelled sweet from new plaster and pine wood. From the spacious living room, Mama thoughtfully walked into the kitchen, visualizing where the stove and cupboard would be. Opening the stair door, papa beckoned her on, pausing on the stairway. Proudly he said "See this closet! It's something extra we hadn't planned." Actually it was a square hole in the wall above the cellar steps, with room to store a couple of quilts. On upstairs he led her through the four cheerful bedrooms. In the master bedroom, the one with the double windows facing the east, Mama hesitated. With a troubled look she asked "Where are the closets?"

"Closets are an unnecessary expense," he explained.

"But we drew them in our plans."

"The carpenters convinced me that this was easier to install, and much cheaper," he said pointing to a board nailed horizontally across one wall. Protruding from it was a row of spike nails. "There's one in each bedroom."

Fury welled up inside Mama. How perfectly horrid the rooms would look with the family's droopy clothes dangling from nails on the wall! Couldn't Papa realize that these were modern times! That they had planned real closets! She bit her tongue to keep from saying what was on her mind. Even her own mother hadn't had to put up with nails. At least her father had provided wooden pegs! Sick at heart, she suddenly realized that every special feature they had planned in the house had been omitted.

Papa's stock answer, as she questioned him was "The carpenters convinced me I didn't need it," or, "It was a foolish frill."

Mama's heart lifted when she saw the ample shelves in the pantry where pans of milk could cool, and she appreciated the cellar, underneath the kitchen, with, its rock walls and dirt floor, and enough shelves for bottled fruit, crocks of preserves and buckets of lard and molasses. In the beams overhead were spike nails for hanging bacon slabs, cured ham and dried herbs.

Papa saved one little surprise for the last. In the northwest bedroom downstairs, was a doll-house sized door. Opening it, Mama saw the rough underside of the stair steps, spike nails protruding from them. If dresses weren't too long, they could hang here. So, in all of this big, eight room house, this little miniature was really her only closet! Airing her disappointment would only have cast a pall of gloom, and this was to be a day of rejoicing. Compared to the drafty granary where they had lived before moving in with Aunt Alice, this was a castle.

The family moved into the new home in January 1912. Although Mama never confessed it to Papa, the absence of closets always rankled in her heart. Years 99 later, at the time Winferd and I were building our home, she related the above incident to me. "Alice," she said, "a woman should be on hand when her home is being built. If she isn't, the carpenters will talk her husband out of every thing she wants."

Winferd's mother, who was with us at the time, said "She's right. I had to be right there to get what I wanted when Hen built our house, and I did get clothes closets. When I insisted on a bathroom, Hen complained 'We're not millionaires.' but I stayed on the job and we got it."

All we had was outdoor plumbing down by the barn.

But our home was a happy one. On winter mornings when we were small, we were awakened by the sound of Mama shaking the ashes down in the kitchen stove. After the kitchen fire was made, she started a fire in the living room stove. Soon there was a warm spot for us to race to after we had dressed in the arctic zone upstairs. It is hard to visualize, unless you've been there, how cold a house can get during the night when the last whisper of heat dies with the dying embers after the family has gone to bed.

Papa couldn't chop wood, so that chore fell mostly to Mama and my older sisters. Try as I would, I could never swing an ax good enough to make the chips fly. And speaking of chips, they were mighty important. Without them, kindling a fire was difficult. Mama claimed to be the world's champion chip sifter.

Flickering firelight lent to the coziness of winter evenings. That, and our one kerosene lamp, furnished our lights. Some of our neighbors were "two-lamp-families."

At supper time, Mama often went to the pantry for more bread or milk, taking the lamp with her. The living room moved with weird shadows as she left, and then was dark. Then the fire in the little heater danced all the more merrily. On nights when there was no fire, we sat in the dark. It was a dark dark. There were no street lights or car lights to filter in from the outside. The only outside lights were stars or moon or lightning. On drizzling nights, nothing. The only way to comprehend real darkness is to crawl into a tunnel and feel your way around the bend. When Mama carried the lamp into the back part of the house the living room was too dark to even talk. We sat around the table smothered in black velvet silence, until the long, funny shadows backed away at her approach.

Shadows were an animated part of winter evenings. With our fingers and hands we made shadow pictures on the walls of dogs, horses, rabbits and cats. With the lamp positioned just right our animals would wiggle their ears, twitch their noses or bark. Actually they were quite classical.

Shadow games were popular at parties. The boys sat in a dark room and the girls were in a room with the lamp. A sheet hung over the doorway in between. Pantomiming in front of the lamplight, the girls cast silent shadows on the sheet. Each boy picked out his partner for the next game by identifying her shadow.

One night Mama and Papa were invited out. It was the only night I can recall being home without them. We actually had a whole, unsupervised evening to ourselves. When Mama and Papa came home, there, boldly traced in charcoal on the white front room walls, were the silhouettes of all of us. Our task the next day was to wash the walls.

1010 The early years in the house that Papa built were probably much the same as that of the first settlers in America. We were on the very tail end of an era. I marvel that I should have been privileged to live the old life style before the world exploded into the new. Hurricane had no electricity, no pipeline, no automobiles and only one telephone. Airplanes, radios, etc. were undreamed of so far as we were concerned.

But Hurricane did have one modern marvel. In March of 1914 Charlie Petty opened a moving picture show hall. It was run by a gasoline motor. When they cranked it up the "putt, putt, putt" could be heard all over town. Mama let me go one night with my sisters Annie, Kate and Mildred. They had to pay a nickel but I was only four, so got in free. The picture trembled and flickered a lot. Men in white overalls were painting a house. Charlie Chaplin, with his funny duck walk, blundered beneath the ladder and a bucket of paint fell upside down over his head. I cried and ran home, but my sisters stayed. They laughed at me when they got home and said I shouldn't have left because no one really got hurt, it was only a picture.

Grandma Isom built her cute little brick house next door to us. Grandma was as much a part of the family as Mama or Papa or any of the rest of us. She had her special rawhide bottomed chair with a cushion on it, and her corner at the table. She cooked on our kitchen stove and ate all of her meals with us, except when she had company, and then she served her guests on her own polished table, on a fine linen cloth set with elegant china, silverware and crystal.

I was her legs, trotting back and forth between houses, carrying the butter dish, pickles or preserves. Her friends were the satin and lace bosomed, talcum faced, kid curler1, kid glove and kid shoe variety, and they called me "little Alice." They usually picked me up, smothered me to their bosoms, kissed me and said "She looks just like Evadna." I hated to be kissed.

"She's a chatter box and has a wild imagination," was Grandma's usual retort.

"Grandma," I asked one time, "do you wish I was an umbrella so you could shut me up?"

"No," she answered. "Now say your little piece then run along home."

My "little piece" was one she had taught me. I recited, "I am a little chatterbox. My name is Alice May. The reason why I talk so much, I have so much to say." The ladies were delighted, mostly because I was going home.

In contrast to Grandma Isom's house of old English finery, the house that Papa built had bare, pine board floors. Mama braided scatter rugs to make it homey. Uncle Jake Crawford made our dining table. It's the same drop-leaf table that stands in the front room of the old home today. After Uncle Jake sanded, stained and varnished it, it gleamed like a mirror. The lounge, desk and the wash stand where the water bucket and wash basin stood, were made by John Hinton, a furniture maker from England. Our few rawhide bottomed chairs were made by my great grandfather Samuel Kendall Gifford. Our iron bedsteads and other chairs were freighted by team from the railroad depot at Lund, Utah and probably came from Sears & Roebuck. The desk was a two pieced affair, the bottom part standing high enough for me and my sisters to play paper dolls under. The sloped lid covered a bin where catalogs, or anything else we wanted to get out of sight, could be stashed. The top part had doors that concealed pigeonhole compartments, and stood so tall that the whole of it towered above the living room.

1111 One blustery day I climbed upon the lounge to look out the window. A man sauntered down the sidewalk past our white picket fence.

"Mama, who is that man?" I asked.

"I don't know," she replied.

Craning my neck to get another look at him, I thought, "Oh my, he must have come from the other side of the earth. He must be from China." Never before had I seen anyone that Mama didn't know. In Hurricane, everyone knew everyone.

On September 3, 1914 Mama had a cute little baby girl. She was the second baby born in the house that Papa built, but I don't remember anything about when Edith came. She was just there like the rest of my sisters. What puzzled me was that the new baby's birthday was one day earlier than Edith's, still Edith was two years older.

Now Mama and Papa had six girls in a row! Aunt Ellen said it was a shame the new baby couldn't have been a boy. I didn't think so. I knew exactly what the folks should name her: Elva. Elva Crawford was the prettiest person I had ever seen. Her eyes and hair were dark and her skin fair. She was as nice a cousin as a girl could ever have. If Mama and Papa would name our new baby Elva, then she would be pretty and nice. I coaxed them to and they didn't say they wouldn't. At Sacrament Meeting I listened, and when Papa named our baby LaPriel, I scrunched my eyes tight to squeeze back the tears. LaPriel was an ugly, ugly name and I'd never, never call her that. What's more, I'd never tell any of my playmates what her name was. I was embarrassed. Then a funny thing happened to the name. It got nicer every day and before LaPriel even learned to goo, I knew Papa had named her right.

A chill autumn wind was scattering the poplar leaves. Barefoot days were over. Will and Maude Savage of LaVerkin, drove up to our gate in a buckboard and delivered a woven rag carpet to us. We'd never had such a luxury before because it took many rags and many rag bees to tear, sew and wind enough balls for a carpet. This was our one and only. Will's Aunt Adelaide was the weaver, and his mother Mary Ann the rag inspector. Adelaide wouldn't weave anything that might make the carpet lumpy. (Adelaide and Mary Ann had walked all the way from Council Bluff, Iowa to Salt Lake when they were little girls, and their mother Ann pushed a handcart.)

Mama piled wheat straw on the living room floor and the new carpet was stretched tightly over it and tacked down. Edith and I tumbled and bounced upon it. The floor was so springy that I felt like I was walking with bent knees. So let the wind scatter the poplar leaves. The house was snug and cozy.

Footnotes

- Kid curlers were made from soft, flexible wire covered with kid skin.

(1915)

1111 Papa was a blessed man, surrounded by women! He had always been surrounded by women. He was the only boy in Grandma's family, and his sisters, Ellen, Alice, Mary, Kate, Annie, Evadna and LaVern loved and fussed over him. Now he had Mama and six lovely daughters. (Mama and Papa never told us we were lovely. They simply didn't talk that way, but we knew they thought so anyway.) Our Aunts Ellen, Alice and Mary lived in Hurricane, and they traipsed to our house 1212 real often to see that "George was eating right." They pampered him and he often reminded us with a grin, that he was "the cutest little boy along the river." Just imagine what Mama had to put up with! All that adulation, plus his special little side dishes at the dinner table and all.

Papa took all of the fussing for granted, as though it was his just dessert. He played his role with dignity, and set the rules that our household had to abide by. Although his feet could not run, his voice reached everywhere, giving instructions or laying down the law. He was the disciplinarian. Mama executed his orders.

We got more training at the dinner table than anywhere else. Papa, Grandma and Mama were a trio. Grandma always said, "Now mind your manners," and Papa would say, "Don't take anything on your plate you cannot eat." Mama put the food before us and silently ate.

Once when I couldn't finish the molasses on my plate, Papa said, "It looks like your eyes are bigger than your belly," and Grandma added, "When the pig gets full, the slop gets sour." My plate with its puddle of molasses was set on a pantry shelf, and the next meal it was set before me. Before I could have anything else, I had to clean it up. Eating off a dirty plate was punishment. It never happened again.

If I over-estimated and took too much food, I struggled until it was gone. But it wasn't fair to have to eat what someone else put on my plate, like pig rind. Once when Grandma dished up my beans, there was a wiggling, curled up piece of pig rind floating in my soup. The fat side curled out, half clear, jelly like and slimy. My stomach lurched at the sight of it.

"Now you eat it," Grandma demanded. "If you waste it, there'll come a day you'll wish you had it."

We were always threatened with starvation as a matter of discipline. I couldn't enjoy the beans because I knew I had to eat the rind. I'd rather be thrashed. With Grandma sitting next to me there was nothing to do but cut into the detestable morsel and try. The greasy piece stuck in my throat and I gagged. Tears welled in my eyes. Rubbing them away with my fist, I obediently gulped down all of that horrid rind. I resolved right then to never, never force a child to eat what he didn't take.

There was some conflict in Grandma's philosophy, however. Tough as she was about our cleaning our plates, she would still say, "It is better that food should waste than a belly should burst," when we licked up the last morsel left in a bowl as we cleared the table.

To have Papa and Grandma boss us was an accepted thing, but to have Kate think she could do it too, exasperated me. Just because she was five years older than I didn't give her any authority. Annie didn't boss me; neither did Mildred. They were peaceful. Mildred and I cut out paper dolls together and made little houses under the desk when Kate thought we should be doing something else. Kate was a lot like Papa and Grandma. One day when she hit me, I sat down in the middle of the kitchen floor and howled in fury.

"If I bawl loud enough," I thought, "Kate will get slapped!" I yelped a mighty blast, and Mama, walking past, swatted me across my wide open mouth. In shocked surprise I shut up instantly. Without saying a word, Mama had straightened me out.

In the springtime, when the apricot tree was in bloom, our new carpet was taken up. This was part of the spring-cleaning ritual for these were the days 1313 before vacuum cleaners. We swept with a straw broom. On Saturdays, to make the carpet nice for Sunday, the broom was dipped in a bucket of water, then shaken. The damp straw picked up extra dirt and kept the dust down. And now, with sunshine spilling everywhere, the carpet was pulled out and hung over the clothes line to be beaten clean and stored for winter. The straw that had been shiny gold last fall was pulverized to powder, to be swept out and burned. The hush of winter's insulation was gone, and the bright, scrubbed room echoed as merrily as the sparrows in the currant bushes.

The smell of blossoms and the song of the birds put a wanderlust yearning within me. Frank Beatty's family lived kitty-corner across the street from us. Mildred Beatty was my playmate and she had relatives living in Leeds. One Saturday morning I wistfully watched her Pa hitch their team to the wagon.

"Alice, would you like to go to Leeds with us?" Sister Beatty asked.

"Oh yes," I gasped.

"Run and ask your mother," she said.

I ran across the street, but I was afraid Mama would say no. We never went anywhere but to Virgin, Kolob or Springdale. I wanted to go with Beattys more than anything, and couldn't bear the thought of being refused. Slipping into the house, I hid behind the front door with my face to the wall. "Mama," I whispered, "can I go to Leeds with Beattys?" "Yes you can go," I answered softly. Racing back I said, "Mama said I could go."

I should have enjoyed my first view of the other side of the earth, but I didn't. My conscience nagged me. It was dark before we got home. I took my scolding because I knew I deserved it, but the terrible thing was the nightmare I had after I went to bed. All night long the "bad man" chased me in his long legged underwear. He was big and flabby fat, pale and bald headed except for one gray wisp of hair that waved when he ran after me. The whole night through I barely managed to keep out of his reach.

I had tasted the wages of sin and was relieved to see daylight streaming in through our bedroom window and to hear the resounding ring of Papa kissing Mama.

Papa's and Mama's bedroom was down the hall from ours, and always when he awoke in the morning, his kiss reverberated through the upstairs rooms, sounding like the ring of Uncle Lew's hammer on the iron tires of his wagon wheel. Although I couldn't see, I knew exactly how Mama's face looked. Papa wore a big, bushy mustache, and his kiss was much the same as being kissed by a haystack. His lips never met Mama's because she always screwed her mouth away from him, giving him lots of cheek which he smacked with a merry sound.

He also puckered up after every meal and leaned toward her at the table, planting his bristling affection upon her cheek, and we watched with pleasure, because Mama's mouth was drawn half way across her face to the opposite ear.

My sisters and I came in pairs. Annie and Kate were a team and slept in the southwest bedroom, Mildred and I in the northwest bedroom and Edith and LaPriel in the northeast bedroom just off Mama's and Papa's big southeast bedroom. Mama and Papa had a feather tick on top of their shuck tick. When we piled into their bed we almost sunk out of sight. Our beds were crackly corn shucks.

Papa was surrounded by girls, including our playmates. Uncle Lew and Aunt Mary Campbell's family lived in the next house east of us, and Uncle Marion and Aunt Mary Stout's family lived in the next house west of us. Venona Stout and Iantha Campbell were a little older than I but they played with Mildred Beatty and me, and they were very important people in my life.

1414 When strangers came to our house, Edith would crawl back against the wall under the lounge and stay until after they left. Once she stayed there almost all day.

Papa was a loving patriarch. He called the family together daily for family prayer. Our days began and ended with all of us on our knees together.

(1916)

1414 The desk in the front room was a hazard. It stood on legs high enough for the baby to toddle under without bumping her head, and the cabinet on top teetered precariously when both doors were open, so Mama put the top part on the floor in the north room. It made a cool counter top for the pans of milk in the summer.

This was our first summer in Hurricane, and the upstairs bedrooms were like a furnace compared to Kolob, so we slept downstairs. Edith and LaPriel slept on the floor in front of the desk top. One morning, as they played on their bed, they hung onto the desk doors and it toppled, spilling the milk on them. Looking like drowned rats they spluttered and bawled. Their hair was matted with slathers of cream and their nightgowns were plastered to them. They were a ridiculous sight in their puddle of milk.

It didn't seem right to not be going to the ranch, but summers in Hurricane brought new discoveries. I learned that July fruit is not always bruised. When Uncle Ren's boys brought apricots and peaches to Kolob, the fruit arrived bruised, oozy brown and delicious. I thought it grew that way and I loved the bruises.

Hurricane had been celebrating Peach Day since 1913, but this year was our first time. The fruit was spread under the shade of the trees on tables made of planks. Melons, peaches, apples, plums and grapes were heaped high. People even came from Cedar and St. George in their wagons. Indians pitched their camp north of town. This was a two day celebration. On the afternoon of the second day, the melons were cut and everyone ate the fruit display. How jolly it was! Dozens of wagons. with teams tied to the side of them, were parked on the north end of main street where Marzell Covington lives today. Horseshoe pitching and other sports were in progress, when from somewhere in the direction of LaVerkin, a strange roaring and popping was heard. The horses moved uneasily, snorting and tossing their manes. Then a chugging vehicle appeared, laying a trail of dust, puffing clouds of smoke from its rear. Wild eyed, the horses reared on their hind legs and squealed. Men hung onto the horses halters to calm them. The vehicle came to a stop where the crowd was the thickest.

"It's an automobile, an automobile," some kid shrilled.

Wow! If we'd been on Kolob, I might never, never have seen one! It made a terrible noise, and smelled awful, but it ran without horses. Wagon covers and buggy tops were white, but this vehicle was black topped. The wheels had wooden spokes, were smaller than wagon wheels and had rubber tires.

Mr. Fox owned the car, and he offered to take passengers for 10¢ a mile. Five people could ride at a time. Grandma gave each of us a dime and I sat in the front seat by Mr. Fox. All the way to the flour mill and back I sized up the car's interior. It had isinglass windows rolled up like blinds, and a bristling coco mat on the floor. Mr. Fox had a mole on his right cheek with three hairs sticking out. Maybe that's why they called him Mr. Fox. My, how I wished I had another dime!

1515 In September I went to the Beginners in the same room with the First Grade. My sisters went to school in the Church House and in the Relief Society building, but we were in Robb Stratton's building that was supposed to be a store, on the corner of what is now 112 West and State. You had to be seven to go to the First Grade. My cousin Josephine Spendlove was our teacher.

In the winter we were either too hot or too cold, depending on where we sat from the pot bellied stove. Probably that's why we were dressed like cocoons.

"Guess what?" I piped one evening at supper. "We had a program in school today and I sang a song all by myself."

"You did!" Mama exclaimed.

"What did you sing?" Grandma asked.

"I sang 'Oh that chicken pie, put in lots of spice. How I wish the goodness that I had another slice.'" With a happy sigh, I settled back waiting for the family's praise. Instead, everyone grinned, then someone whispered, "She can't even carry a tune." I was crushed. Later, when Miss Spendlove asked me to sing, I refused.

Coming home from school each day, we walked past the loafers, or what some folks called the Spittin' an' Whittlin' Club. The front of, or the side of Charlie Petty's store, depending on the season, the wind or the sun, was the gathering place for the farmers. After school, we'd pass them, leaning against the store, or squatting on their heels, enjoying the afternoon break before chore time. Some of my playmates used to stop and beg their dads for nickels. Impressed, I decided to try it.

"Papa, can I have a nickel?" I asked, expecting him to say no.

Instead, he dug into his pocket and handed me one. I felt sheepish. I didn't really want the nickel.

Walking into the store, I surveyed the jars of hard tack candy and the packages of gum. I couldn't spend the money on something that would be eaten up and forgotten, so I bought a yard of inch wide, red, white and blue striped ribbon that I took to my room. Occasionally I'd spread it across my lap, or thoughtfully run it between my fingers.

A fun pastime was making up little plays and charging ten pins for the ticket. One afternoon we noticed the door to the wooden church house ajar, an open invitation to go on stage. We'd just cast the parts to Red Riding Hood, when Clark West's frame filled the doorway. He was the janitor. With the terrible voice of authority, he demanded to know why we were there. I was scared. He stood with his feet spread wide and I observed how long his legs were and how much room there was between, so in a sudden longing for freedom I darted between his legs and ran home.

Meat markets and refrigeration didn't exist. Grandma and Papa had cattle "on the range," and when a beef was butchered the word was spread through town. Papa always had his beef animal done in the early morning before the flies awoke, and people came from all over town with their little pans to buy a cut of fresh meat. We usually ended up with the heart and the liver. Mama stuffed the heart. We called it "Yorkshire Pudding" but it was more like sage dressing than a pudding. Trying to eat the liver is what made a vegetarian out of me.

Thanksgiving day, plank and saw-horse tables were set up in the church house and covered with snowy white table cloths. People came in buggies and wagons, 1616 bringing their good food and pretty dishes. We walked through the ankle deep snow. My feet were soaked and my toes ached, but nothing could dim the joy of the only community Thanksgiving I can remember.

Grownups had a good thing going in those days. They expected total respect from young folks, and they seemed to get it. An oft repeated axiom was, "Children should be seen and not heard." This was simply a matter of discipline. Also, it was an accepted custom, that at any large dinner, grownups ate first. Youngsters, out of respect for their elders, must learn patience and wait their turn. So it was with this community Thanksgiving. The grownups ate while we got our shoes still more soggy by trying to make a snowman. When our fingers got purple, we collected around the stove. Our good behavior was rewarded by the full and loving attention of the grownups as they waited on us as we were seated around the second table.

A few days after Thanksgiving, my sisters brought their baking powder cans tinkling with pennies and nickels and dumped them out onto the table to be counted. Wide eyed I watched and listened to their chatter about paying tithing.

I didn't have any nickels or pennies. I didn't even have an empty baking powder can, but I knew a little about tithing. I had seen the loads of tithing hay being hauled to the tithing barn, and I had watched Mama push the firm, yellow butter from the wooden mold onto the wrapper for "tithing butter". And our chickens laid "tithing eggs."1

"Mama, when can I pay tithing?" I asked.

Mama's dough covered hands stopped still in the big pan where she was mixing bread. She looked at me for a long minute then smiled. "My goodness, you are getting to be a big girl, aren't you? Why of course you want to pay tithing."

After the dough was washed from her hands, she said, "Come with me".

I followed her to the chicken runs, where she scattered a little wheat. Greedily, the chickens flocked around her and she slipped her hands over the wings of a young, black rooster.

"Here," she said, handing him to me, "hold him while I tie his legs."

From a bunch of used binding twine that hung on the corral fence she selected a short piece. Securing the rooster's legs she said, "You've been a good girl to help feed the chickens, so you can take this rooster to Bishop Isom for tithing."

My sisters giggled at the rooster squirming in my arms, as I announced I was going to the bishop's with them. I hugged my rooster as we walked the six blocks to his house and the rooster chuckled back at me.

When Bishop Samuel Isom saw us coming through his gate, his front door opened wide. His ample front was made for hugging children and his big mustache made his laugh seem extra jolly.

Seeing the rooster he asked, "Ho, ho, what's this?"

"He's a tithing rooster," I announced.

"Ah, he's a fine one," the bishop said, taking the chicken from me and setting him down on the porch.

1717 The Bishop sat at his roll top desk and my sisters paid him their nickels and pennies and he made out our receipts. As he handed them to us he gave us each a loving pat.

"Will you please read my receipt for me?" I asked, looking up at him.

"Gladly," he replied. Taking it from me he read, "Alice Isom has voluntarily contributed to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, one rooster."

I tingled all over. The church was so big and I was so small, still I had contributed to it!

When we got home Mama gave me an empty mentholatum jar. "You can keep your tithing money in this from now on," she said.

The jar was shiny and warm from the scrubbing she had given it, scrubbing off the label. The translucent milk white glass was beautiful to me. I loved that mentholatum jar and used it all through my childhood.2

Footnotes

- Eggs were considered a woman's petty cash. Women tended the hens and turned her surplus eggs in to the store for "script." There were "tithing eggs" and "Sunday eggs." The two-roomed, brick Relief Society building in Hurricane, Utah was built with "Sunday Eggs."

- Story "The Happy Tithe Payer", originally published in Friend, May 1976, p. 2.

(1917)

1717 ZCMI used to give Grandma a box of creamy, soft, swirly chocolate at Christmas time. The box was big, but so was Grandma's posterity, and I knew one piece was all I'd get. And this piece I licked fondly until there was nothing left but the good smell on my fingers. Sometimes Grandma gave me the empty fluted cups and breathing deeply I'd bury my nose in them. She knew what a rare treat this was to all of us.

One day when we were at Grandma's house with our cousins, she brought out her chocolate box. Breaking the cellophane from the shiny, pink box, she removed the velvet ribbon. Our mouths watered. She lifted the lid and chocolate aroma filled the room. To each child she passed her treasure. Breathlessly I waited and finally she held the box before me.

"Do you want a chocolate, Alice?" she asked.

Trying not to appear too eager I timidly replied, "I don't care."

"Well," she retorted, "If you don't care, I'm certainly not going to waste one on you."

And she didn't. I was crushed. But the lesson she taught me has never been forgotten. I learned that I'd better let it be known that I do care, one way or another, about everything of importance. I also learned to say, "Yes please," or "No thank you."

Grandma's house had plush carpets of red roses and dark green leaves on a rich brown background. Light, filtering through white lace curtains, was reflected in the soft sheen of her polished furniture.

Edith and I were her dusting girls. Sometimes our cousin Virginia Campbell helped. Edith was Grandma's favorite duster because she sat tirelessly under the dining table, working the dust cloth into every curlicue of the carved legs. Her fingers also went round and round through the fancy iron work under the sewing machine. I detested fussy details. Still, Grandma gave me as many lemon drops and peppermints as she did Edith. Edith knew she deserved 1818 more and she and Virginia helped themselves from the shoe box of candy on the marble top table in the parlor. Those frosted lemon drops were as tempting to me as to them, but my nagging conscience held me back. So Edith and Virginia snitched freely and I shared the blame.

Grandma didn't blame gently either. Once she accused me of using all of her black shoe polish.

"Grandma, I didn't do it," I said.

"It's no use for you to tell me that, for I know full well you did," she snapped.

I stood up for myself the best I could, but she said I was being disrespectful and sassy. I was humiliated, because Aunt Mary Campbell was there. I hated being scolded in front of company. One look at my shoes would show that they never had been shined, except with soot, and that rarely.

Tears stung my eyes and my throat ached. I was trying hard not to cry. Aunt Mary put her arm around me. The squeeze of her hand and the look in her eyes told me she knew I was innocent. I resolved that when I became a Grandma I would never tell a grandchild they did something if they said they didn't.

Grandma braided my hair snake-braid. The idea was to weave each lock of hair in so tightly that it couldn't come undone. She wore a thimble as she braided, claiming it helped her do a neater, tighter job. That wasn't the real reason. The thimble was for thumping my head when I wiggled. I had to sit like a statue. She pulled my hair so tight at the temples that she almost braided my skin in too, and slanted the outer corners of my eyes up, and the corners of my mouth as well. A scowl would have been impossible because the muscles were stretched the opposite way. I became so tough headed I could have been hung by my braids without feeling it. But my hair, as Grandma lamented, was like snakes, crawling all of the time. Mama called it wiry. No way could the ends of my braids be fastened so they would stay. Once undone, the braids unraveled like pulling a thread on a knitted sock. That meant more head thumping from Grandma's thimble.

No squirrel ever stored more diligently for winter than Grandma did. In our granary she kept a forty-gallon wooden barrel with grapes pickled in molasses and water, and one for pickling corned beef and one filled with brine for cucumbers. All winter she dipped into these barrels, doling out goodies into her little brass bucket for us to take to her friends. On Saturdays or after school she would send me pattering across town with the shiny little bucket taking her offerings to Grandma Spendlove or Grandma and Grandpa Hinton or to Albert Stratton or Lizzie Lee.

Grandma ate her meals with us except when she had company. Then she cooked on our stove, but served her guests on her own pretty table with her elegant dishes. Once when she was taking currant pies from the oven, she dropped one. It spilled from the plate in a broken heap. I was glad, because she said, "You young ones can have it." No pie ever tasted so good as the one we ate from the kitchen floor. Her daughters used to say, "Ma is so saving, that if a fly lit in the molasses, she'd lick its legs before turning it loose." Papa said she was thrifty.

Even though Grandma and Papa did most of the disciplining, there were times when Mama took a hand, and when she did she made it good. She wouldn't tolerate 1919 our quarreling or fighting. If two of us got into a scrap, she cut three willows, one for each of us and one for herself.

Raising her stick, she'd say, "All right, if you two want to fight you're going to do it right. Now you hit each other or I'll hit you."

My arm would go weak in the elbow. I couldn't begin to lift my stick. Looking at my sisters then back at Mama I'd whimper, "I don't want to fight."

"Do as you're told and hit each other," she would demand.

We'd both be sniveling by now. "We don't want to fight," we'd howl.

"Then kiss each other and behave yourselves."

Kissing each other was the worst punishment of all, but it was either that or the tingling of the willow. Usually it was the latter. But Mama didn't have to use this method on us often. It was drastic enough to make for lasting peace.

But the world wasn't at peace. Grandma digested the Deseret News each evening and we got a review of the news the following day at meal time. Often when I was busting to talk, Papa would say, "Shhh, Grandma is talking."

A war was going on. The Germans, especially Old Kaiser Bill, were the bad guys and the English, with the British Fleet were the good guys and they were scrapping over France. Little Belgium was the stomping ground.

When our stable was cleaned, the manure was always pitched out of the two east windows. The mounds dried and we used to play one mound was Bunker Hill and the other Golden Hill. We wore a powdery trail in between as we ran back and forth. Now these piles became France and Germany and we played "Kaiser Bill went up the hill to kill the king of France. Kaiser Bill came down the hill with bullets in his pants."

As Grandma reported the news, vivid pictures built up in my mind. The British and Germans were deadlocked somewhere in Belgium. Neither side could advance, so they dug trenches for themselves. Parallel lines of trenches ran clear across northern France from Flanders to Switzerland. "No man's land" was the strip between. I pictured the Germans burrowing in their muddy trenches like mean little gophers. Grandma's reports were awful! Millions of lives were lost in those trenches by machine guns, poison gas and liquid fire.

Stories of German submarines filled the news. Grandma was aghast at the news when the Lusitania was sunk, drowning over a thousand people. The Lusitania was a British ship of war, but was carrying just plain people, a lot of them Americans. President Woodrow Wilson let Germany know we didn't like this one bit, but Germany sank eight more American Ships. In a single week they sank eighty-eight ships. (History of the American People by David Saville Muzzey, pages 631-637)

President Wilson said, "It is a fearful thing to lead this great and peaceful people into war … but the right is more precious than peace." (Muzzey, p. 631)

On April 6, 1917 the United States of America declared war on Germany! Our country was involved in World War I. (Muzzy 632)

Fortunately, the world continues to turn, war or no war, and springtime brings sheep shearing time. The Goulds Shearing Corral upon the Hurricane Hill was fast becoming the biggest operation of its kind in the world, so the story goes. Aunt Alice and Uncle Will Spendlove ran one cook shack, cooking for thirty or forty men, and Thad and Lizzy Ballard ran the other cook shack, cooking for the 2020 same number of men. Uncle Will came to Hurricane almost every day for water and supplies, and Thad did too. Thad had a water tank that was as long as the bed of his wagon.

Papa decided it would be a good family outing to go to Goulds so he borrowed Uncle Ren's team and wagon. To ride anywhere was a treat to us. Mama put a denim quilt over a shuck tick in the wagon box for us to sit on and packed the grub box. She sat up front on the spring seat beside Papa.

I was so excited I could hardly contain myself. I thought of the good picnic Mama had prepared and of seeing Aunt Alice and Uncle Will and of watching the men shear sheep.

When Papa slapped the reins, on the horses backs, the wagon creaked and swayed as the horses pulled into the ruts in the road. Going up the Hurricane Hill was scary, because the dugway was narrow and steep, but I savored each turn of the wheels. Once on top, the horses settled into an easy gait and I stretched out on the bed, enjoying the protection of the tightly stretched wagon cover over the bows that the beating sun illuminated but did not penetrate. The horses jogged along and the wagon wheels ground pleasantly in the dirt, lulling me to sleep. When I awoke, we were going down the hill and Papa was pulling back on the brake rope.

"Aren't we going to Goulds?" I asked.

"We have been to Goulds," one of my sisters replied.

"But I haven't," I cried.

"Oh yes you have. You just didn't wake up," someone said.

Crawling over to where Mama sat, I said, "Mama, I haven't been to Goulds, have I!"

She looked at me in surprise and put her arm around me. "Bless you," she said, "I guess we forgot to wake you."

"Oh Mama," I cried, "you didn't have the picnic without me did you?"

She looked stricken. "I'm afraid we did. There were so many people, I guess we didn't notice you were still in the wagon asleep."

I didn't just cry. I howled broken heartedly. How could anyone do that to me! How could they, when we simply never, never went anywhere! "I didn't even get to see the shearing corral," I bawled.

Everyone was sorry, but I knew I would never get to go again, and I didn't.

My disappointment over the Goulds trip was deeper than I can express. It had been so good just to smell a wagon cover again and to hear the clopping of horses. A longing for the annual trek to Kolob was revived, stirring within me almost to the point of obsession. I yearned for the sight of bluebells, pink phlox, squirrels and pine trees.

I'm sure Mama felt very sorry about the slip-up on the Goulds trip too, so when Aunt Ellen and Uncle Ren Spendlove invited me to go to Kolob with them for the summer, Mama and Papa consented to let me go. I was transported with joy. I loved every turn of the road, camping under the open sky, watching the dying embers of the campfire, hearing once more the sound of horses munching grain in their nose bags. With a happy heart I drifted off to sleep.

The early morning climb up the mountain brought us to Heaven! A Heaven of long needle pines, the smell of sage and racing through the meadow with Venice and Velma.

2121 Aunt Ellen made corn bread for supper. She put a piece on my plate with yellow butter melting through it. I took one bite but could not swallow. I looked at the dear faces in the lamplight. WHERE WAS MAMA? WHERE WERE MY SISTERS AND PAPA? My throat tightened. I picked up my plate and headed for the door.

"Where are you going?" Aunt Ellen asked.

With a gulp I answered, "I want to eat my corn bread outside."

It was still twilight. I sat with my back against a pine tree, my plate in my lap. I tried to eat but couldn't. Tears were splashing on my dress. Why? Here I was at my very own Kolob, sitting against my favorite tree, with my favorite food on my plate, still I was crying. Digging a hole in the sand, I buried the bread and then I cried hard. In that moment I knew Heaven would never be Heaven without my family.

The next day Lafe and Tennessee Spendlove galloped in on a little buckboard to deliver some things to Aunt Ellen. They were returning to Hurricane that afternoon, and I begged to go with them. Venice and Velma coaxed me to stay, but I would not.

When I got home, Hurricane looked hot, dull and dry. I realized that I had run away from Kolob. This time I fell desperately ill. Heartbroken, a homesick longing as big as the earth and sky seemed almost to crush the life out of me, a longing to bring together the two dearest things on earth to me, my family and Kolob. And this could never be.

It was quarterly conference and the house swarmed with relatives from "up the river." I was on the bed in the northwest bedroom and was going to die. I knew it and I knew Mama and all of the relatives knew it. This was the end. Then I saw the concern on Mama's face and I said, "Mama, if you will get Brother Barber and Brother Jepson to help Papa administer to me I will be better." They came and after the administration I was well instantly.

On June 5th, my cousin Ianthus Campbell died. He was one of the babies that had inspired my sisters to pray for twins. Now Iantha was left without her twin the same as I was.

Ianthus used to play ball in the street with us. Our balls were made of tightly wound carpet rags, stitched on the outside with carpet warp in a honeycomb stitch. Our bats were pieces of board whittled narrow at the handle and wide as a paddle—the wider the better our chance for hitting the ball.

Sometimes Ianthus teased me. Once I got so aggravated I hit him with the garden rake. I couldn't hit him good because the rake was too heavy for me to swing, but I got him good enough to make him run home bawling. Uncle Lew said he was going to take me to Kolob and use me for coyote bait. Now Ianthus was gone and he would never pitch a ball to me again, and I wished I had never hit him.

But Uncle Lew and Aunt Mary still had one boy, Marcus, the same age as Edith. The nearest thing Papa had to being a boy was me. Grandma said I was a Tomboy, and Papa encouraged it. When Sam Pollock came to play checkers, Papa used to get me to shinny up the porch poles. Sam would say, "Ah George, she can climb as good as any boy." I wasn't interested in being "as good as." I wanted to be "better than," so that's when I started climbing to the peak of the barn. When Grandma 2222 saw me walking along, the ridge of the barn roof, she fluttered into the yard screeching, "Aaalliss, come right down before you break your neck!" From my perch she looked wonderfully small down by the woodpile, and I loved her clucking and ruffling her feathers over me. I climbed down, but I knew I would climb up again because I wanted Papa to brag about me. Then there was the mulberry tree in front of Grandma's house. The top limbs were even higher than the barn. When Grandma saw me swaying overhead she went into a most satisfactory dither and I climbed down to please her. Between her spasms and Papa's bragging I felt famous.

We used to sing a song that went something like this:

My sister wears a velvet dress and ostrich feather hat

And white kid gloves and shiny shoes and all such things as that.

She goes to parties, matinees and dances all she can,

But she can never do the things I'll do when I'm a man.Chorus

A girl can't be a cowboy, or run away to sea,

Or be an Injun fighter, like I intend to be,

So I don't care what she may wear, it never makes me mad,

For I shall run the country when I'm big like Dad.

This song made me wish I was a boy. Sometimes I honestly resented being a girl.

Although it had been years since Grandma had closed her store in Virgin, she could still buy wholesale from ZCMI. In fact, ZCMI not only gave her chocolates every year, but they also gave her a rich looking satin dress piece every summer when she returned to Salt Lake to visit relatives and friends. And always she returned with a big cardboard box filled with white canvas slippers, a pair for each of her granddaughters. She bought them for ten or twenty cents a pair. With each pair she gave us a half-moon shaped piece of chalk to keep them white. We only wore them on the 4th and 24th of July and on Sunday. The rest of the time we went barefooted.

Sometimes we made moccasins out of the backs of old overalls, to protect our feet from the scorching earth and from the grass burs. Our winter shoes—and there was only one pair a year—had high tops that either laced or buttoned. A button-hook hung by the door between the front room and the kitchen. Saturday nights we turned a stove lid upside down and with a rag and spit we rubbed soot on our shoes, blacking them for Sunday.

Frank Beatty traded property with Charlie Workman and moved his family practically off the earth. They moved at least two miles away in the Hurricane fields. That meant that I lost Mildred Beatty for a playmate. But Workmans built a house a half block up the street and I got a new playmate, Eloise. Eloise's sisters Hazel, Flora and Delsey used to read stories to us. When they read the people in the stories came alive, they were so full of expression. Eloise's brothers Carl and Eldon treated us like grown-ups and entertained us, and Sister Workman would put out big glass fruit bowls filled with dried malaga grapes and paper shelled almonds on Sunday afternoon. We loved to visit at Workman's home.

In the fall, a most disgraceful thing happened! When school started they put all of the dumb little six year olds in with us. The "Beginners" was discontinued and the new kids started right out in the first grade! It wasn't fair! 2323 With a wounded, superior air, we looked down on those little "babies" the whole year through. But one thing eased the blow, and that was that it made us kind of distinctive for we were the last of the beginners, and the new little kids were the first, first graders to be only six years old.

The new school building was not quite finished, so we started the first grade in the Relief Society building.

Great things were going on in Hurricane. Tall power poles were being planted down every street. How exciting it was when electricians began wiring our house! My little sisters and I were right underfoot to grab every metal slug the men dropped to the floor. They were the size and color of nickel coins.

The electric power was turned on in Hurricane in September 1917. Every corner had a street light and lights shone from every home. How beautiful it was!

Light globes were delicate, exquisite things of thin, crystal clear glass, with delicate wires inside, glowing first red, then bright yellow when the power was turned on. A globe hung from a drop cord in the center of each room in our house. The front room, kitchen and hall had wall switches—push buttons in a copper plate. In the other rooms the lights were turned on at the globe. We were fascinated with the magic that took place when we pushed the button, but Papa sternly said, "This is no play thing. You will wear out the switches." He made a strict rule that the lights were to be turned on only once each night, and we could take turns at that. When it was my turn, I looked forward with excitement all day for the coming of night. We boasted and bragged to our playmates about the brightness of our lights. To out-do us all, Iantha said their lights were so bright they had to open the door to let a little dark in.

Burned out light globes became treasures. Women crocheted lace coverings for them and used them as ornamental curtain tie-backs.

But electricity was undependable. We didn't put the kerosene lamp away, because with every gusty wind or rain squall, the power went off. Each time Mama lit the lamp, Papa remarked, "Another cow must have stepped in the Santa Clara Creek." That's where our power came from.

On the morning of October 30th Grandma came from Mama's bedroom. "Good morning girls," she said, "the stork brought you a little baby brother in the night."

Papa came into the room with a funny look on his face. It was a grin with tears in it, like he was laughing and crying at the same time.

"Come quietly and you can see your new brother," Grandma said, going into Mama's room ahead of us.

Mama smiled at us and pulled the covers back so we could see the little creature that was bundled beside her. Well! He certainly wasn't any beauty. He was bald headed as a jack-o-lantern. If he had waited one more day he would have been born on Halloween. "If I were Mama," I thought, "I'd stick to girls."

What I couldn't quite figure out was why everyone who came to our house made such a fuss over Papa. All of our Aunts kissed him and said, "Well George, at last you have a fine son," and the corners of Papa's mustache twitched and he batted his eyes like something was in them. Not one soul said, "Well George, you have six lovely daughters!" Except Sam Pollock. When he came to play checkers with Papa he'd sort of say it in a round about way. He'd say, "Ah George, someday the devil will pay you off in sons-in-laws."

Our brother was named William Howard for a whole line of grandfather Williams going back on both sides, and for our Howard ancestry that came from England. 2424 Papa had Howard in his name too, and since George had been given to my twin, our new brother got the Howard part.

During all of the excitement of Hurricane growing, and our family growing, Grandma still kept us posted about the war with Germany. We heard about, saw and felt the effects daily. Every man between the ages of twenty-one and thirty had to register for military service. Looking back, I don't see how our country could have had such a jaunty air about going overseas. Our soldiers joked and laughed and sang, making the war appear to be a romantic adventure. Snatches of their songs went something like this:

Johnny get your gun, get your gun, get your gun,

Take it on a run, on a run, on a run,

Make your daddy proud of you, and your own red, white and blue.Over there, over there, send a word, say a prayer,

For the Yanks are coming, their hearts are strumming,

The drums are drumming everywhere.… We're going over …

And we won't be back till it's over, over there.

In every little church house in every little town farewell parties were held. The entire town gathered for the farewell party when the first soldier boys left Hurricane. Sweethearts and mothers were in tears. I remember Josephine Spendlove, Mattie Segler and Annie Workman, sweethearts of Elmer Wood, Ren Spendlove and Claude Hirschi. The girls were dressed in sheer blouses, and their lacy camisoles with tiny pink or blue ribbon bows showed through. They looked so romantic to me. Through their smiles, they shed just enough tears to make the occasion sweet and sad and I got a lump in my throat. The following two songs were sung and continued to echo in my mind, because we heard them many times afterward:

SMILE AWHILE

Goodbye means the birth of a teardrop.

Hello means the birth of a smile.

Over high garden wall, the sweet echoes fall

As a soldier boy whispers goodbye.Smile awhile, you kiss me sad adieu.

When the clouds roll by I'll come to you.

Then the skies will seem more blue

Down in lover's lane, my dearie.

Wedding bells will ring so merrily,

Every tear will be a memory.

So wait and pray each night for me

Till we meet again.

SO LONG MOTHER

So long my dear old mother, don't you cry.

Come, kiss your grown up baby boy goodbye.

Somewhere in France I'll be dreaming of you,

You and your dear eyes of blue.Come, let me see you smile before we part.

I'll throw a kiss to cheer your dear old heart.

There's a tear in your eye, don't you sigh, don't you cry.

So long mother, kiss your boy goodbye.

The following day people gathered on the streets to wave goodbye as our soldiers left town in a Model T Ford, on their way to Camp Lewis.

(1918)

2525 In 1917 the Hurricane and LaVerkin towns bought water rights from Toquerville and both towns began to look something like Northern France. With picks and shovels men dug trenches down every street. But these were not grim trenches like the ones in France. These were happy ones where kids could race, whooping and laughing and hollering, after the workers had gone home for the day. What fun we had, until it was discovered what a lot of dirt we were knocking down for the men to shovel out again, then we were forbidden to play in the trenches anymore.

In the trenches wooden pipes with wire coiled around them were buried, and by January 1918 water flowed through them. We had a tap under the cherry tree close to the kitchen door. Up to this time we drank "cistern" water. Papa owned a cistern in with Uncle Lew and Uncle Marion. It was built just below the canal. It had boards over the top to keep kids and critters from falling in, but every little while it had to be cleaned to get rid of polliwogs, snakes, snails and moss. Cistern water was piped to the corral and the cow's trough was slick and green.

With the new water system, our drinking water was no longer murky, but crystal clear, and the taste took some getting used to. People called it "Toquer-Bloat."